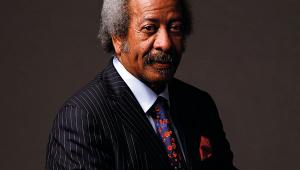

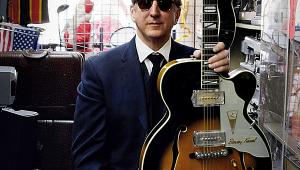

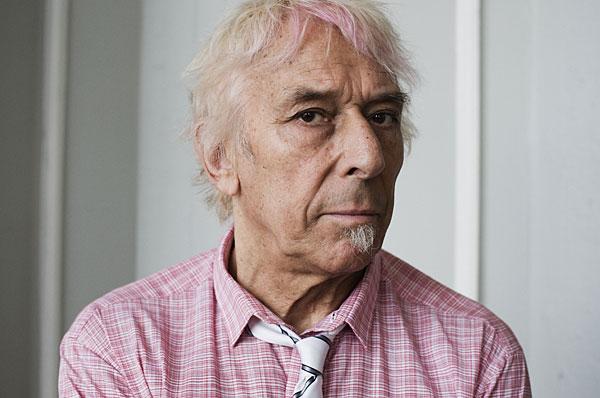

John Cale

See that jittery bloke over there, the one who appears to be severely chemically imbalanced, the one shouting his head off waving around the half-drunk bottle of Stolichnaya? He's the boss. He's in charge. He's the producer. He's John Cale.

And where you find yourself is in a barely finished new studio in Shoreditch, The Strongroom. And it's where Cale has been called in to somehow coax, cajole and bludgeon an album out of his old Velvet Underground cohort Nico.

Mini Dramas

Now Nico, as legend has long established, is deeply devoted to a heroin habit that's not exactly conducive to the creative process. In fact, she's not actually here right now – she's been banished for a few days so the rest of her crew can get on with it. 'It' being to write, arrange, produce and record an entire new album from scratch inside three weeks.

Nico has no 'songs' as such, just scraps of melody with no words, or sometimes vice versa. At the best of times, as keyboard player James Young so eloquently puts it in his splendid book, Songs They Never Play On The Radio, 'Nico's songs were like mini-dramas – they depended on phases and silence. There was no inherent rhythm that suggested itself, and no sense in which she kept strict time. Thus a rhythm track would have to be created against a vocal line that wavered and faltered...'

And that was when the going was good! But the going was anything but good right then. James Young again: 'One musical idea or phrase would become instantly superseded by another and yet another until they were all subsumed beneath a 3am alcoholic blur...

'Cale would record layers of ideas, colours and textures, to play with later at the mixing stage. There were endless arguments. At the end of three weeks they just had to leave it and walk away...'

The album ends up being called Camera Obscura. It comes out on Beggars Banquet in 1986, Nico's last one before she falls off her bike in Ibiza and dies. And amazingly, it's not half bad. Though Cale, of course, has done better. Way better. Nico's debut, The Marble Index for instance, the one that established her as the goth of all goths, largely due to her stentorian Germanic vocals and the harmonium that Cale had procured, her instrument of choice from then on in.

Ego Battles

'She was the most awkward of all songwriters,' Cale remembers. 'My relationship with her was always the same. She was slightly lost. We always had fights, physical at times. but at the end of all this, it was a wonderful moment of relief and, for her, the realisation that she'd made something extraordinary.'

Ladies and gentleman: meet John Cale, the man they call when the weird need out-weirding and the task in hand appears too great an achievement for any mere mortal. But before we get down to marvelling at all the era-defining records John Cale has shepherded into being, some brief background…

Born in Garnant, South Wales, in 1942, he studied piano and viola, moving to London in the early '60s for a stint at Goldsmiths College, earning him a scholarship in New York. There he became attracted to the avant garde, taking part in John Cage's marathon piano experiments and joining LaMonte Young's drone ensemble The Dream Syndicate.

In 1964, he met Lou Reed at a party and the pair resolved to form a band. That band was The Velvet Underground and Cale stuck around for their first two seminal LPs: 1967's The Velvet Underground And Nico and the following year's White Light/White Heat – before monster ego battles saw him quit and go solo.

He also guested on Nick Drake's Bryter Layter and Eno's Another Green World among many notable cameos, and was seduced into producing for others when the money began to run short.

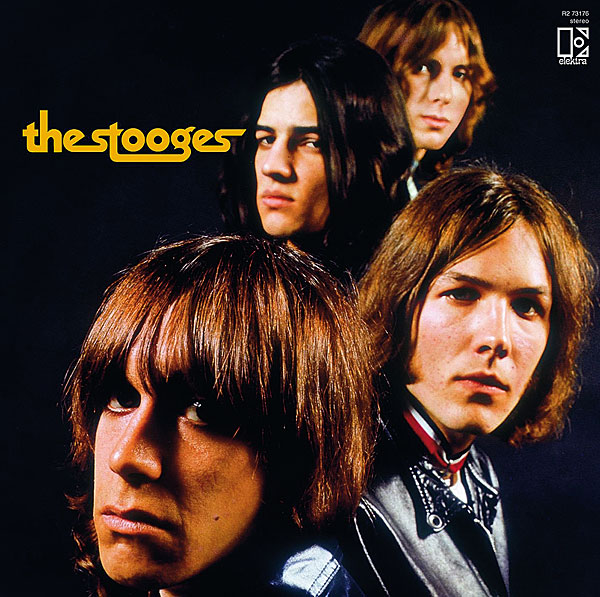

Apart from Nico's Marble Index and Desert Shore, he also helmed The Stooges' 1969 debut, the album that pretty much set the blueprint for the punk revolution to come.

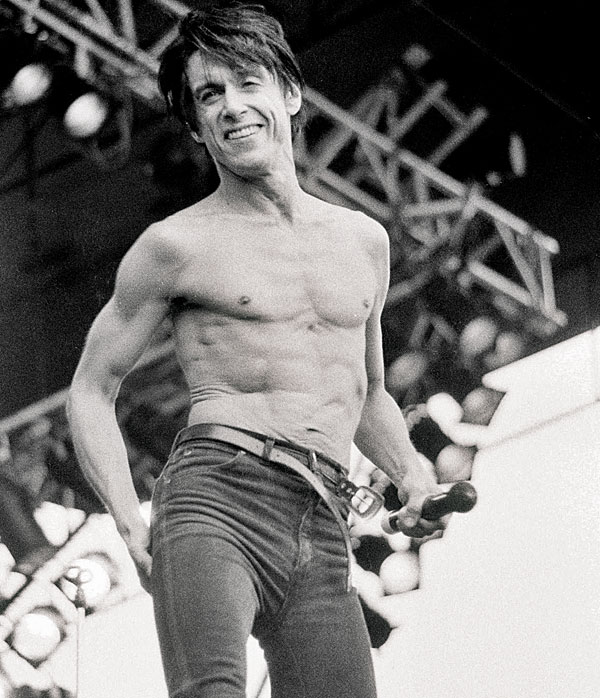

'I wanted to work with them because of their live show. It was the way that Iggy handled the crowd. And you go, "Wow, how am I going to put this in a record?". A silly question. You just make the music. You don't worry about the visuals and all that.

'I knew the energy level that was there live and what a magical presentation it was. But when you have five days in the studio to do a record, you don't have time to worry too much about how does this compare to live recording, or whatever.

'Iggy was very together – he came in and gave me a sheet of lyrics that had been very carefully written out. And it was incredible seeing him in the studio: he'd be climbing all over the amps and the desk like a mad animal, while the band just played as if nothing out of the ordinary was happening.' Cale got to join in the fun. He's the one stabbing that one note on the piano throughout 'I Wanna Be Your Dog'.

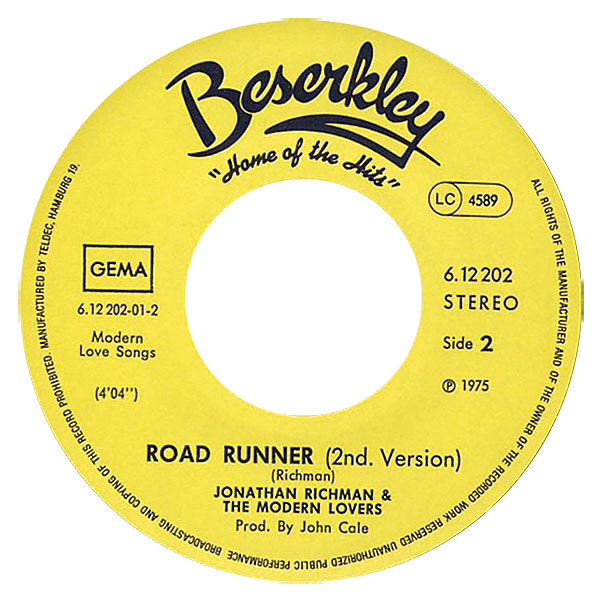

Self-Destruct

His next project was what you might call a glorious failure. Young Jonathan Richman had been such a Velvet Underground fan that he'd followed them everywhere and when he got the chance to record his own band, The Modern Lovers, in 1972, Cale was obviously top of his list to produce. That was about as good as it got. But then, according to Cale, 'The minute Jonathan signed, he immediately went on self-destruct. I went to Bermuda to record their debut album for Warners. But as soon as it got down to the time to record, anything you agreed with, he immediately contradicted. It became a horror show in the studio.'