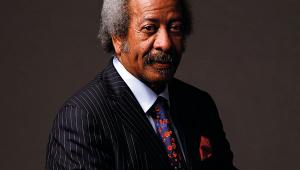

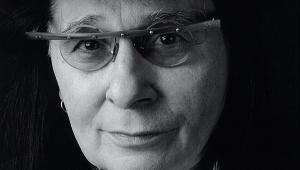

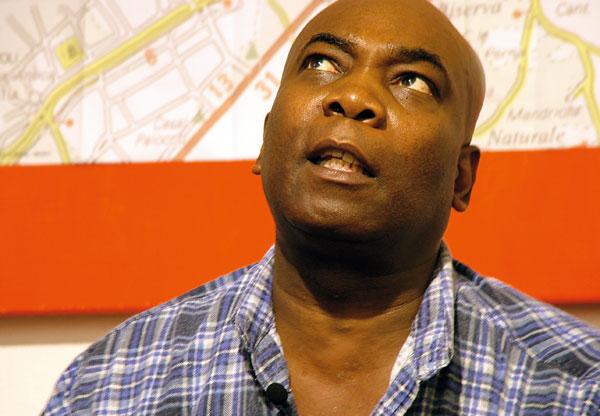

Dennis Bovell

It's the 13th of October 1974, a date remembered in some circles as Black Friday. The facts are somewhat sketchy but it seems a couple of police officers decide that some black dude is driving suspiciously through Cricklewood in London. They pull him over and are about to arrest him when he legs it into The Carib Club. Six officers give chase and grab him in the toilets. They're bringing him out with a bit of a struggle when some club-goers, mates of the pursued, tackle the cops, stabbing one and setting the fugitive free.

Trial And Error

The next thing anyone knows, hundreds of police swarm the place and a dozen people are arrested, including one Dennis Bovell, a 21-year-old from Barbados who's been living in Wandsworth, South London for nine years, carving out a reputation for himself as the guvnor of the Sufferah's sound system and as a leading member of Britian's premier reggae group, Matumbi.

His arrest hinges on the fact that, while the fracas was taking place, the police testify that the club deejays were encouraging the crowd to do the cops in. The fact that there were three sound systems in competition that night, and that only one, not Mr Bovell's, was mouthing off, shouting 'Kill the police!', seemed not to matter when the case came to court.

'It was all attributed to me,' Mr Bovell recalls today. 'I never thought people would lie in court like that. They even put their hand on the Bible! The trial lasted six months and at the end, nine people were acquitted and three people had a hung jury, of whom I was one.

I wasn't proven guilty but instead of affording me what British law says, they moved the goalposts and said, "You're gonna be retried for this". And so I had a retrial.

'It lasted nine months altogether with the two trials. At the end of the retrial at 12 noon the jury went to decide and by nine at night they still hadn't decided. So the judge said, "If they don't decide by ten we're going to throw it out, we can't try you three times". At five to ten, the jury came back and said, "Ten of us think he's guilty, two think not guilty". The judge said, "That's good enough for me – three years in jail".'

'I went to Wormwood Scrubs and while I was in there – I was in for six months of that three-year sentence – I appealed to a higher court. The appeal judge said, "This guy should never even have been charged with that, there's no evidence. Let him go". So they let me go that day, I was free, I was on the news, I was a big star and my band was going to be in the charts next week!'

School Studios

Dennis Bovell, as you may have gathered by now, is a remarkable chap. He picked up his production skills in the music studios at school where he also met some of his Matumbi bandmates.

'The word Matumbi was the most African-sounding name we could come up with,' he explains. 'Having been brought up in London, there was no African history, it was Richard III and Charles I. Henry VIII, what's that got to do with me?

I wanted hear about Shaka Zulu and people like that. So we started to investigate African history and show our Africanness by choosing an African name. It's ironic because that name came from an English lesson. We were doing O level English, and it was a novel called Mister Johnson by Joyce Carey. In that book there was a Sergeant Gallup, and he had an African woman and her name was Matumbi, and the description of her was the most beautiful.

'We became political because at that time there was an English politician called Enoch Powell, who was the father of the National Front.'

In The Red

There was quite a deal of resistance to the band from record labels, as the few British reggae acts at the time were expected to do crowd-pleasing cover versions. Mr Bovell had other ideas and, working as an engineer at Gooseberry Studios, he traded his wages for studio time and began doing his own stuff, sometimes under the pseudonym Blackbeard or African Stone or The Dub Band or Dennis Curtis or The 4th Street Orchestra.

Touring and recording with Matumbi, running his own sound system and creating his own new dubplates to play alongside the dubs being imported from Jamaica, Bovell was busy enough as it was. But upon his release from jail, he found himself some sort of hero and a producer in demand by default.

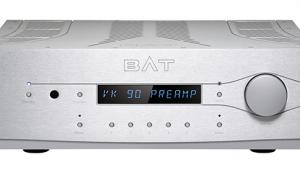

'Every time we went into the studio, there'd be arguments with the engineer trying to describe what kind of sound we wanted. At that time it was, "You can't have that much bass, you're crazy. It'll blow the speakers. You can't have your treble like that. Everything must be very flat. Zero, zero, zero. You can't go above zero". So I'd just go, "Stand aside. You see those knobs? I know how to twiddle them... The sound is in here and I'm going to put the sound that I want on my record".

'Can you imagine saying to Jimi Hendrix, "That's in the red"? So the sound engineers would go, "But it's in the red!". I wanted it in the red 'cause it's not loud enough. Also, it was the battle of ears against eyes. Your ears would say it's good, whereas your eyes would say, "No, it's in the red". So what? Cover your eyes and the dials. It's sound, it ain't film. Use these. If it sounds good and you like it, walk with it.

'Anyway, after many arguments with engineers and recording studios, I decided to be a producer and dictate what the sound sounds like. That was my reason for becoming a producer.'