Recording the Classics Page 2

And there they stayed for the best part of another 20 years.

Elsewhere in the book, recalling sessions with the Polish-American pianist Artur Rubinstein at Kingsway Hall, Culshaw writes: 'Rubinstein wanted the piano to be relentlessly loud throughout, irrespective of dynamics, tone quality, or whatever Mozart might have written for the orchestra. "I am an old man", he whined to the engineers when I introduced him. "Please make me as loud as you can".'

'On the last session Rubinstein brought along one of his children, who was obnoxious enough to comment that there wasn't enough piano. This was finally too much for the normally taciturn first engineer, Kenneth Wilkinson, who inquired coldly, "Enough for what?".'

Short Measure

Culshaw also writes about Austrian conductor Karajan. 'He was deeply interested in recording technology' he recalls. 'If he did not know as much as he thought he knew, he still knew a great deal more than all the other conductors put together.

'Nobody… ever questioned Karajan's right to do exactly what he wanted. He moved everywhere with a circle of sycophants… He arrived one day with a raincoat over his arm, which he promptly offered to Gordon Parry, the senior engineer, to carry for him. Gordon simply ignored the gesture… Karajan never tried that trick again.

'The first work he wanted to record was Strauss's Also Sprach Zarathustra [but] there is no organ in the Sofiensaal [in Vienna]… We found one in a military chapel at Wiener Neustadt, some distance away from the city… but the organ was too flat for our purposes. We found an organ tuner who was prepared to shorten the organ pipes to our requirements… the problem was to find an organist discreet enough not to talk about what we had done. In the end the part was played by my assistant on Zarathustra, Ray Minshull, who had studied the organ during his university days.'

Hi-Fi Revenge

'Seven years later Stanley Kubrick chose the opening of [Karajan's] Zarathustra as the recurring musical element in his film, 2001: A Space Odyssey… The ultimate irony was that Decca's condition for releasing the tape to Kubrick was that no credit should be given to Decca or Karajan on the film itself.

'It was an example of Decca's decline. Nobody in [Decca's] management had even the remotest idea of what classical producers actually did… Lewis never came near a recording studio… and neither did Rosengarten… Lewis not only lacked the slightest conception of how a modern recording was made: he had no idea at all of the skills he was employing or what people actually did. To him they put up mics, pushed coloured buttons on a machine and were probably overpaid for doing so.'

Culshaw took revenge on music and hi-fi pundits: 'With Salome [we suggested] that we had invented an entirely new approach to operatic recording… We called it "SonicStage"... It was greeted as a major technical development, whereas there was not a jot of difference between Salome and any other opera we had recorded in Vienna for the past three years.'

General Shoddiness

Kingsway Hall is long-gone but remembered with rosy-tinted reverence for its acoustic. Those who recorded there had other views.

'We were so used to its general shoddiness', wrote Culshaw, 'that we scarcely noticed that after several hours in the hall one was covered with a thin film of grime which rose from coke-burners in the basement. Yet despite its innate hideousness and the fact that underground trains rumbled to and fro directly beneath the hall (the sound that the trains made had to be "sucked out" of the low bass frequencies when tapes were dubbed for disc) nothing altered the fact that it had the finest recording acoustic in London.'

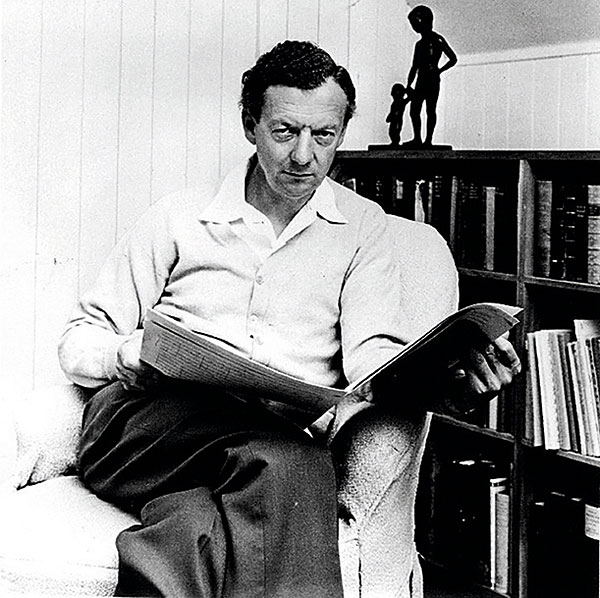

In the early 1960s Culshaw produced Benjamin Britten's War Requiem, conducted by Britten himself.

'A small mountain of rehearsal tapes had been made, and I immediately imposed a security clamp on them, for there was never any intention of releasing such material to the public; but I thought that one LP of excerpts, carefully edited, might make an unexpected birthday present for Britten.'

Tapes Destroyed

A new member of staff, John Mordler, was told to sift through 16 hours of War Requiem rehearsal tapes. Once edited, the discarded sections were then destroyed and the 50-minute master locked up in the safe until later in the year.

Britten was duly given his birthday LP, but Culshaw soon had second thoughts.

'I think it was a well-meant miscalculation on my part. [Britten] was not at ease and when, many months later... I asked him if he had listened to any of it he evaded the question. I never brought it up again... I thought that some day, and to someone, it will be a valuable document, in the sense that it shows his method of rehearsal and gives some indications of a composer's special insight into his own work.'

Aside from some excerpts [Decca 4757511] the full rehearsal session has not been commercially released.

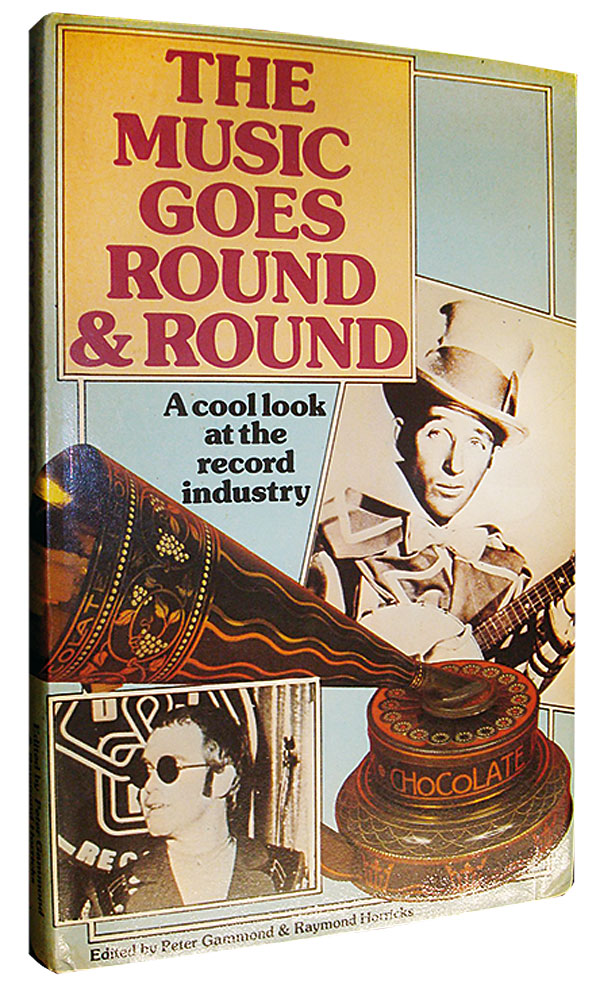

The Music Goes Round And Round, 1980, by Peter Gammond and Raymond Horricks is generally lightweight but has a good chapter by EMI's Christopher Bishop. He, too, recalled working at Kingsway Hall, before recording stopped in January 1984, after EMI and Decca had said no to buying the building.

'The control room is under the stage, and completely airless... By present-day standards the mixing console was of the simplest, but to me it looked unbelievably complex. The recording machines were in the basement, even further into the bowels of the earth, and the operators talked to those in the control room by a highly temperamental talk-back system. It was particularly inclined to go wrong if a producer wanted a playback after a session.'

Bishop had firm views on editing. 'My view is that if a take of a passage lasting, say, ten minutes, has two or three mistakes, or sections not up to the conductor's standards, there is no harm in covering those with sections from other "takes"... There is, however, another way of editing, and that is to build up a performance bar by bar. It is utterly deplorable… the editor's skill can make an incompetent artist seem competent. There is an old story of an artist whose work had been cobbled together saying, on hearing the edited tape, "This is good. I didn't realise I'd played so well". To which the producer replied, "You didn't"'.