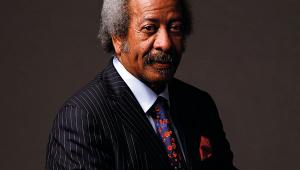

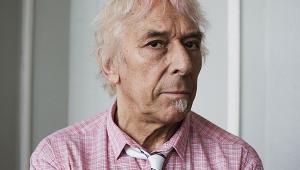

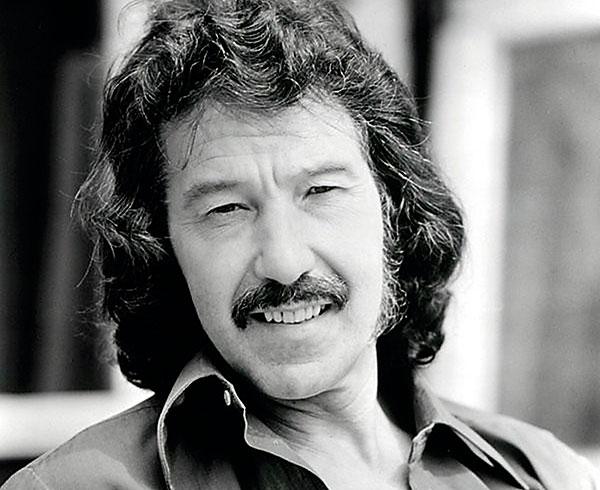

Norman Smith

The group, it's fair to say, were getting a right rollicking. Their hair was too long, their clothes too shabby, their manners a mite lairy, and as for their equipment... it was a shambles, falling apart.

The producer was having a stern word and when he piped down, his assistant picked up where he'd left off, banging on about etiquette and volume and punctuality. On and on and on they went... until, at last, a merciful pause. At which point the producer, the very acme of good manners, asked the lads if they had anything at all to say in response.

There was a moment's silence and then, assuming the audition an utter disaster, the youngest of their number piped up: 'Yeah... I don't like your tie!'. The producer sat stock still, then grinned. The assistant nearly fell off his chair.

Unsung Hero

And so it was that a relationship was born that changed the world forever. The group was The Beatles, the young 'un George Harrison, the producer George Martin [HFN Jun '16] and the assistant a fellow called Norman Smith, an unsung and under-appreciated hero of the British Beat Boom and beyond, an aberration we're about to put right.

Norman, who John Lennon would later affectionately refer to as 'Normal' because of his insistence that the group's performance in the studio remain with the dials the polite side of the red, was indeed one of those wonderful suit and tie company types who kept the late '50s/early '60s music industry ticking over efficiently within taste and budget. Born in 1923 in Edmonton he'd already done a stint in the RAF as a glider pilot and tried his hand as a jazz drummer in The Bobby Arnold Quintet when, in 1959, he happened upon an advert placed by EMI in The Times newspaper for an apprentice sound engineer. With a young family to support, he tapped into a hitherto underused rebellious streak, lied about his age (they wanted candidates up to 28 years old; he was six years too old to apply) and gained an interview whereupon he thought he'd blown it when he revealed he considered Cliff Richard 'nauseating', only to find his interviewing superiors secretly in agreement. Two hundred applied, three were taken on. He was one.

Chance Hit

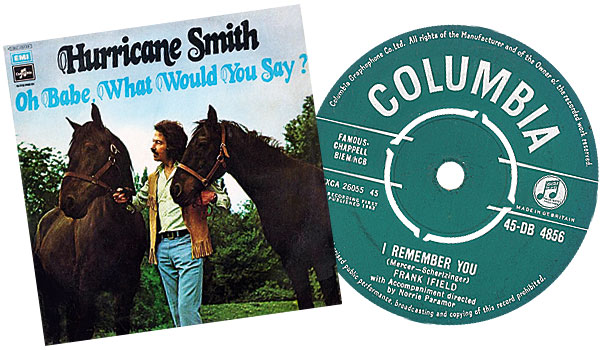

Making the tea, running errands, at 36 years old he found himself fulfilling all the junior stuff, graduating to tape op and then engineer, eventually working on stuff by Manfred Mann, Shane Fenton (later Alvin Stardust), Helen Shapiro, Gerry & The Pacemakers, The Swinging Blue Jeans, and The Dakotas, The Shadows et al. In 1961 he engineered Cliff and The Shadows' 'Young Ones' session but, with chances for promotion extremely rare, he really needed a hit firmly nailed to his name – an event that arrived in the most unlikely of circumstances. Norman was asked to be the balance engineer on the commercial test (ie, the exit interview) for a fading Australian star about to be dumped called Frank Ifield. The producer was Norrie Paramore and the song, an old 1942 Jimmy Dorsey number called 'I Remember You', quickly became a No 1 smash.

Suddenly Norman found himself running the auditions that acts had to endure to gain a recording contract. And so it was that, having been rejected by virtually every other UK label, The Beatles turned up for a Parlophone audition in EMI's Studio 2 on Wednesday, June the 6th, 1962. Norman then took it upon himself to gussy them up into something resembling ship-shape and Bristol fashion, got a soldering iron to their battered equipment and set the tapes a'rolling.

The upshot of the audition for Norman was that he engineered all The Beatles' major releases up until the end of 1965. That's about 100 songs from 'Love Me Do' to 'Michelle', six chart-topping LPs – With The Beatles, Please Please Me, Beatles For Sale, Help!, A Hard Day's Night and Rubber Soul – and nine No 1 singles. His job, as he saw it, was to keep it street while George Martin and the boys finessed, manicured, expanded and progressed their sound.

Calling upon his own experience as a jobbing musician, he recognised that the sterility of the traditional studio set-ups would most likely dampen the excitement the band sought to capture on disc.

Mersey Sound

'Up until the time when I became a sound engineer the other engineers would always use screens,' he recalled, 'so that the separation was good on each mic. But I didn't like that idea for The Beatles. It seemed they would be far happier if they were set up in the studio as though they were playing a live gig.

'I threw all of the screens away, and the Abbey Road management warned me that I was taking a little bit of a chance. But The Beatles performed as they did on stage, and although the separation on each mic wasn't terribly good, it did contribute to the overall sound.

'We also got a bit of splashback from the walls and the ambience of the actual studio, and in my view that helped create what the press dubbed the "Mersey Sound". I'd receive phone calls and letters from America asking how I managed to get all of that sound on tape.'

Yet once the album Rubber Soul was completed, Norman was alert to a couple of crucial changes.

UFO Spotting

The first was that the group were now more than capable of capturing the sound they wanted in the studio without a ton of exterior guidance. The second was that George Martin, frustrated by the trade constraints EMI was forcing upon him, went freelance, meaning there was a vacancy for Producer and Head of A&R.