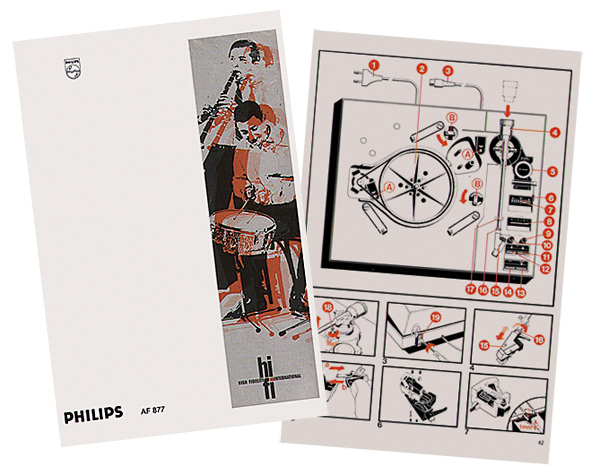

Philips AF 877 Turntable

Sophisticated styling, touch controls and the promise of all the benefits of direct-drive using a sub-platter driven by a belt. Can this late '70s record player really deliver?

Sophisticated styling, touch controls and the promise of all the benefits of direct-drive using a sub-platter driven by a belt. Can this late '70s record player really deliver?

Think of CD players and Philips will be one of the first names to come to mind. This is not necessarily the case when it comes to turntables, even though the company has produced a multitude of models over the years. Its turntable motors could be found in the early Linn LP12 and many other similar designs, yet to most British listeners a complete Philips turntable, like the AF 877 seen here, is something of a novelty.

In the late 1970s Philips was spending a reported £450 million on R&D a year. This, of course, covered all its activities related to electronics, but the budgets were still there to knock out a decent record player or two. Its top models featured innovative technologies, sharp styling and considered ergonomics, a combination that had become something of a Philips hallmark. The key differentiator between its models in engineering terms was something called 'Direct Control' – a new way of accurately regulating the speed of the platter.

Little Belter

The design requirements for effective direct-drive turntable motors are similar to those needed to produce the precision drives found in video recorders. The leaders in this field – Matsushita (Technics), Sony and JVC – were also at the forefront in the development of video machines. Philips was also heavily involved, its N1500 model being the first truly practical video recorder to reach the market. This, and the many models that followed, relied on advanced servo techniques. But unlike the approach taken by the Japanese companies, they were not based around direct-drive motors. Rather, Philips stuck with belt drives for every domestic VCR it made until the V2000 era began, two years after the debut of the AF 877 in 1978.

The principle was simple: measure the speed of rotation achieved not at the motor shaft but at the other end of the belt, where the object to be turned was located. With this method, inconsistencies and variations in power transfer through the belt could be automatically and instantly eliminated, giving the best of both belt and direct drive in one mechanism.

Tacho Sensor

The AF 877, like all Philips Direct Control turntables, has a tacho sensor built into the centre bearing. This returns a signal whose frequency is proportional to the platter speed, so all the electronics have to do is adjust power to the motor in order that the frequency signal is always within closely defined limits. In a way this approach is similar to that used in the company's Motional Feedback loudspeakers – enclose as much of the mechanical process in an electronic feedback loop as is possible.

Plinth 'N' Pick-Up

This may well sound straightforward, but the slow speed of the platter rotation, the inertia that results from its mass and the necessary flexibility of the drive belt (required to ensure the sub-chassis suspension is effective) all serve to complicate matters. Making the action of the servo too rapid would lead to bursts of instability while making it too lazy would mean that it may as well not be there. The critical nature of the final settings can be determined by attempting to run the motor of an AF 877 with the platter removed – it pulses erratically and will not settle. For servicing Philips recommended a small and temporary circuit change to avoid this, which is how finely tuned the Direct Control servo is. From this it also follows that the original platter mat is the only one that should be used with these turntables.

There was more to the AF 877 than just a clever motor. The plinth was cast from the same type of low-resonance resin compound that Sony used and a floating sub-chassis hanging from arched strips of spring steel was employed – an arrangement similar to the one favoured by B&O at the time. Tiny Bowden cables, like miniaturised versions of the brake cables found on a bicycle, were used to link parts of the mechanism across the chassis isolation barrier while touch sensitive controls also made it into the design.

For the cartridge, Philips fitted its own GP412 model. This had been around in various forms since the late 1960s and had become a respected alternative to those Shure had offered in its M75 range. The headshell was an alloy casting secured to the end of the arm with a Philips version of the familiar SME fitting, different to and incompatible with all the standard types of course.

The AF 877 was part of a family of similar decks, which included the AF 677, AF 777 and AF 977. The '677 and '777 were the basic models, semi and fully automatic respectively. The '877 and '977 were also semi and fully automatic versions of a slightly more luxurious offering, the latter adding quartz lock and a digital speed display as well. In Europe it was the AF 777 that was the big seller, being competitively priced and well regarded.