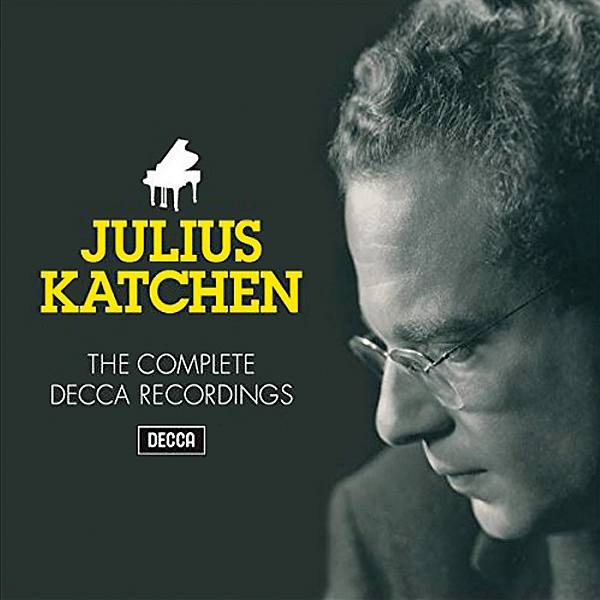

Julius Katchen: Concert pianist

Exasperated by the pianist's fussiness over phrasing, when recording Brahms's D-minor Concerto with the LSO in 1962, George Szell conducting [HFN Aug '18] told him to 'just play the f***ing notes'.

In a way, that's what the American pianist Julius Katchen did – and how! – bringing a formidable structural grasp to everything he played but not, say in the last Beethoven piano sonata or Diabelli Variations (which he recorded twice), seemingly seeking the sublime inner quality which Claudio Arrau painfully struggled to project.

Katchen came from a Russian immigrant background, born in August 1926 and studying at first with his two grandparents in New Jersey. At Haverford College, Pennsylvania, he studied philosophy and his piano tutor at the Curtis Institute was David Saperton (whose other pupils included Shura Cherkassky, Jorge Bolet and Abbey Simon). Saperton made the first recordings of the complex transcriptions written by his father-in-law Leopold Godowsky. As a teacher, his 'insistence on nothing less than keyboard perfection… was hectoring and obsessive'.

After a Mozart concerto debut when aged ten, Julius Katchen was invited to perform with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Then, following concert appearances in Europe in 1947, he decided to live in Paris, where he remained until his death from leukaemia when aged only 42. He disliked the concert managements in the States, which tended to book artists only to play popular programmes, and his return to play there in late 1962 came after a 15-year break.

Katchen's early discography reflects his interest in contemporary composers. The earlier, rather forgotten, LP of Bartók's Piano Concerto No 3, with Ernest Ansermet and the Suisse Romande has remarkable sensitivity and reflects a musical partnership to equal the later Anda/Fricsay [DG] benchmark. Testament has licensed this from Decca [SBT130] along with eight excerpts from Mikrokosmos and Prokofiev's Piano Concerto No 3.

Benjamin Britten asked that Katchen should record his Op.21 Diversions (piano left-hand only) and this was first issued in 1954. Listening to Ravel's Concerto for the Left Hand, made with the LSO in top form under István Kertesz in Nov '68, it's difficult to grasp the fact that you're not hearing both hands! This was Katchen's final recording and would be the last piece that he would perform in concert.

Audience Invite

Julius Katchen's first big project had been Brahms's Piano Sonata No 3, a 1949 US London LP; and he amassed all the solo works and chamber works with Josef Suk and Janos Starker towards the close of his career. In 1959 he made a very fine version of the D-minor Concerto, with the LSO under Pierre Monteux [Decca 460 8282] – Katchen was also the pianist in Monteux's 1957 Paris RCA recording of Petrouchka. But I never thought his Brahms No 2, where János Ferencsik was conducting, was the equal of No 1 – although in a Gramophone on-line tribute the writer Jed Distler relished the unmarked accelerando in the finale's coda: 'Brahms would surely have winked in approval'.

With Friedrich Gulda and the veteran Wilhelm Backhaus under contract to Decca and both at work on Beethoven piano sonata cycles, Katchen only did Op.111 and the Appassionata, although he was not above excerpting the slow movement of the 'Pathétique' for a 1961 stereo Encores LP [SXL2293]. For this disc he found the empty studio 'cold' and invited an audience so that he could give a 'live recital'.

In the Beethoven Piano Concertos and Choral Fantasy [Decca E4758449, a Presto download set] he recorded with the former child prodigy Pierino Gamba (still alive). Here, perhaps, he deserved a more senior conductor, such as Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt. Still, these were well regarded interpretations, produced in the early '60s at Walthamstow. I seem to remember Linn Records briefly licensing part of the set for its RECUT 'audiophile' LPs which didn't really have the 'Decca sound'. These were made by its Swedish distributor High Fidelity in Stockholm – the remake of the Bartók/Prokofiev with Kertesz was reissued as REC 02.

Katchen was recording from the dawn of the long-playing record, working in eight halls or studios until 1969, and like many other artists repeating his repertoire with the establishment of stereo as the norm. We all used to think that the stereos were inherently 'better' but not all was musical gain. Katchen's coupling of Rachmaninov's Paganini Rhapsody with Dohnanyi's witty Variations on a Nursery Tune was remade with (as before) Boult and the LPO. But their 1954 mono proves altogether sharper, more engaging, now that we can compare both.

On the other hand the later LSO version of Rachmaninov's Piano Concerto No 2 is the one to hear. Solti was the conductor and perhaps surprisingly he was far more impressive than Anatole Fistoulari in the 1951 New Symphony Orchestra mono produced by John Culshaw. I've read that this was the first concerto recording to appear on any LP [LXT2595], although discogs.com doesn't support the claim. Moreover the piano writing is sometimes covered by the orchestral balance, while cadenzas sound as though dubbed in from an emptier hall – nothing unusual about that!

No, the remake with Solti – did he conduct any other Rachmaninov? – is a really thrilling collaboration. But while you are stunned by the technical brilliance you admire Katchen's sheer musicianship no less. Should you come across it, the single-sided LP [SPA 505] was preferable to the two previous cuts.

Carnival Time

The big box set detailed below allows you to compare early and later versions of the same work; and the last CD has shellac transfers not published before – also a collaboration with Thea King in Brahms's two Clarinet Sonatas. It's a relief to be spared Beatrice Lillie's ghastly Carnival of the Animals narration, as both with/without options are there! Schumann's Carnaval is there too of course.

Dipping into these CDs and the Audite duo (which has the Liszt Sonata, not recorded by Decca) I was struck by an observation by his composer friend Ned Rorem, that 'his music was photographed not in his brain but in his fingers'. True, sometimes those fingers seemed to be saying 'play faster Mr Katchen!' – the cadenza in Beethoven's Concerto No 4 is but one example – yet what is consistently striking is how thoughtful the playing is.