Halcro Eclipse Stereo Power Amplifier

The original Halcro amp starred in a recent HFN Vault feature but, some 20 years on, the marque is back in the same iconic shape and with the same high tech claims...

The original Halcro amp starred in a recent HFN Vault feature but, some 20 years on, the marque is back in the same iconic shape and with the same high tech claims...

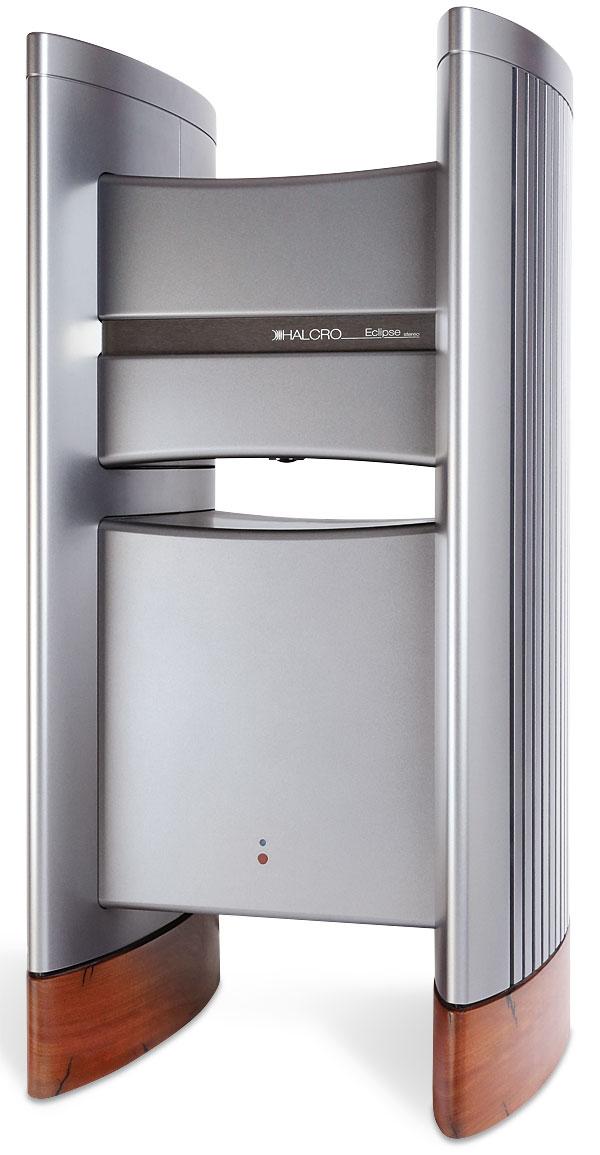

Working out the brand behind the Eclipse Stereo power amplifier isn't hard: not only is the design a modern take on the iconic Australian Halcro amps of the past [see 'From the Vault', HFN Dec '22], but the product itself, with the power supply and amplifier suspended between two solid uprights, forms the letter 'H' – not a trick we've seen other manufacturers attempting!

Selling for £46,000 in the Premium finish of the review unit, or £6000 less for the only slightly plainer Standard version, this latest iteration of a design that started with the original Halcro dm series around the turn of the millennium [HFN Apr '02] is part of a range including the Eclipse monoblocks. They are said by the manufacturer to be 'the new reference in amplification'. Quite a claim.

Origin Story

I say 'its manufacturer' as a lot has happened between those original dm models and the latest Eclipse line. Originally designed by South African-born, Cambridge-educated, adopted Australian Dr Bruce Candy – middle name Halcro – the amps were inspired by his development of metal-detection devices for the gold extraction industry, this microwave and ultrasonic technology forming part of his Minelab Electronics brand.

Halcro was born as a subsidiary of Minelab and was the result of Candy's loathing of any kind of distortion in amplifiers, and his belief that such distortions created 'ghost tones' which, while unheard as sound, could be detected by the human ear. Translating some of the thinking used in those high-sensitivity, super-accurate gold-sniffers, he was able to claim for the dm38 amp 'better than 99.9997% purity of all tones across the entire audio range'. Let's just say Dr Candy was never less than assertive in his claims, but the design went on to be developed further, and by the time of Halcro's last flagship model, the dm88, was definitely one of those 'spoken of in hushed tones' products.

However, that was then, and this is now... After Minelab was swallowed up by military comms company Codan in 2008, mainly for the potential of its detection technology in clearing mines – of the lethal rather than profitable kind – Halcro, a distraction from the operation's main business, was shelved. And on the shelf it stayed, save for a brief licensing project with Vivid Audio, smartly seen off by the (last) Global Financial Crisis, until it was revived by Magenta Audio, an Australian-based hi-fi importer and distributor.

A new company, Longwood Audio, was founded with a team including Magenta's Dr Peter Foster and former Halcro lead engineer Lance Hewitt, and the Halcro brand, patent portfolio, stock and tooling – which had been sitting in an Adelaide warehouse whose lease was set to expire – were acquired.

A Total Eclipse

And that brings us up to date with the Eclipse series, the result of considerable re-engineering, not to mention re-tooling and redesigning that iconic shape, which is now just a little softer and more curvaceous, finished to an even higher standard. The silver anodised casework of the old design, described by one reviewer as tending to 'ring like an old Adelaide church bell', is replaced by much heavier machined-from-solid aluminium, with the two enclosures forming the crossbars between the uprights made from aluminium sheet up to 1cm thick.

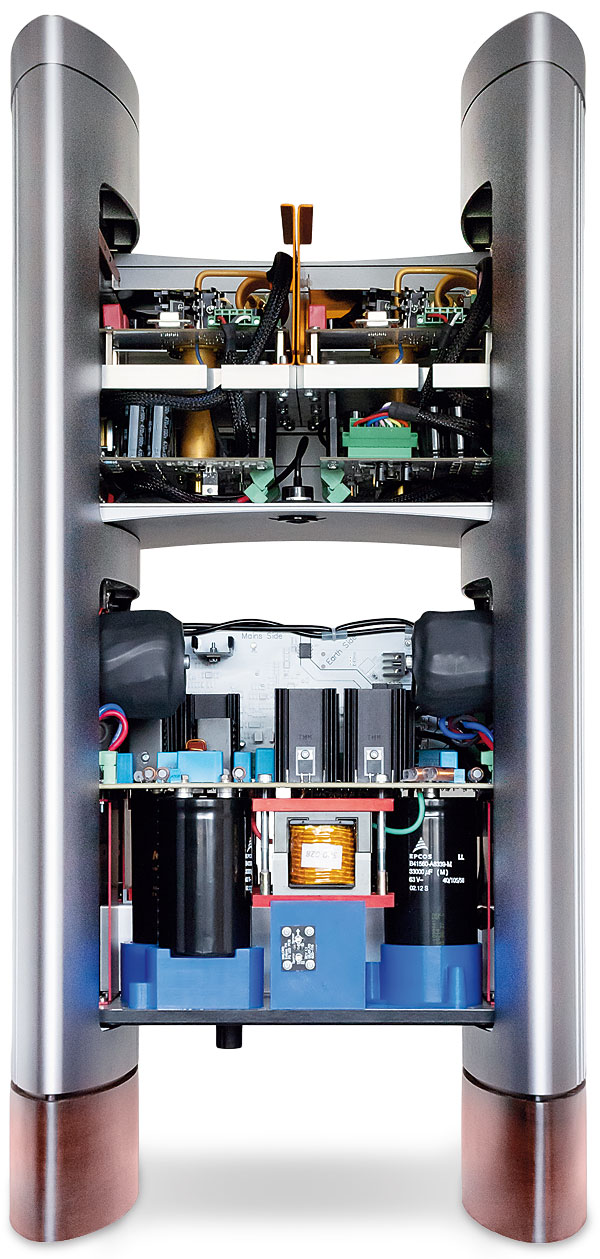

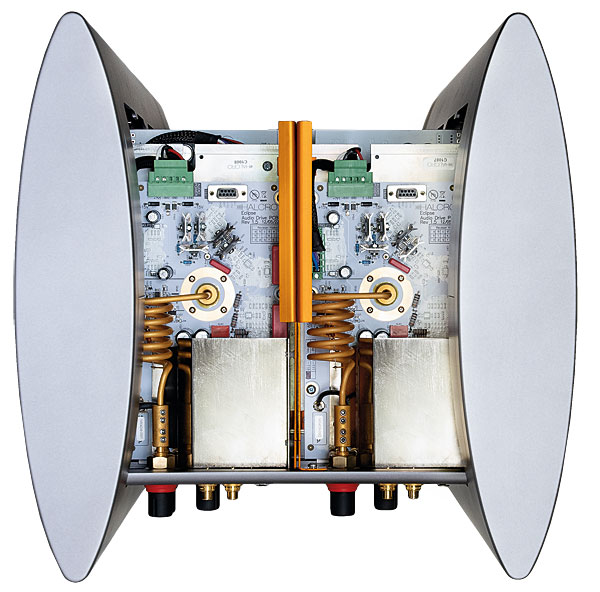

And there's even more to those boxes than meets the eye. The lower, larger housing contains the power supply, compete with IEC mains input and master power switch, while the upper section houses the input and output amplifier stages, each shielded from the others in more aluminium and copper. Every part of the amplifier's structure is hand-sprayed with multiple layers of aerospace-grade paint, and the whole enterprise sits on feet hand-carved from wood by a local luthier – or guitar-maker to you and me. In the standard version the feet are mahogany while, for the Premier version, they're aged Australian Redgum, apparently recycled from century-old fenceposts…

Meanwhile, many circuits have been re-laid and their components upgraded, the new Halcro maintaining the old Halcro's levels of stealth and mystery by painting over parts and enclosing vital sections in epoxy to keep their secrets (or damp them, depending on how you look at it). And with invisible fixings further serving to make the whole thing tricky to take apart – this being an amplifier to play, not to play with – all the owner really need know is where to find the pneumatic switch under the amplifier housing. With a slight hiss, from the switch, the amp moves out of standby (red light) to operational (blue light).