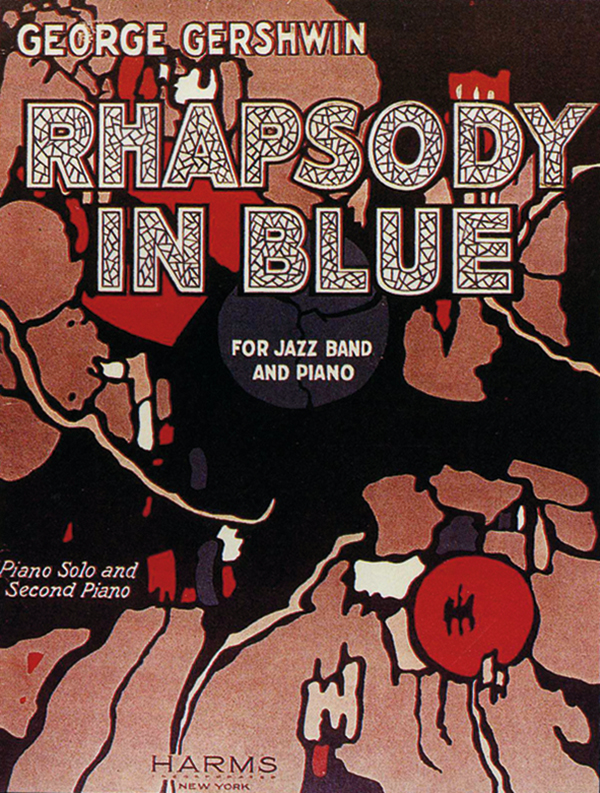

Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue

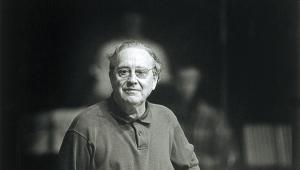

Imagine being George Gershwin [pictured above, in 1937]. There you are at breakfast one day in January 1924, chewing over ideas for your next musical, when your brother reads out an announcement in the newspaper. The impresario Paul Whiteman has arranged a concert on 12 February. The concert will answer the question, ‘What is American music?’, and ‘George Gershwin is at work on a jazz concerto’. This is the first you’ve heard of it.

Gershwin set to work. Lacking both time and experience of orchestration, he drafted in Whiteman’s chief arranger, Ferde Grofé. Gershwin was on a train to Boston when the Rhapsody In Blue took shape, all at once. ‘I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America – of our vast melting-pot, our incomparable national pep, our blues, our metropolitan madness.’ Something like that, anyway; Grofé himself later said that it was his idea to insert the big swoony E major tune halfway through.

Even with the score in something of a scrambled state – shades of Beethoven, half-improvising the Choral Fantasy back in 1808 – the Rhapsody was a smash. Within 1924 alone, it received another 80 performances. A hundred years and at least a hundred recordings later, we can see (or rather hear) the joins where the piece creaks. When Gershwin got around to writing a concerto proper, the following year, he took a good deal more time and care over both form and orchestration.

Above: Cover of the original piano sheet music for Gershwin’s Rhapsody In Blue, issued by Tin Pan Alley publisher Harms Inc.

However, that piece – Concerto in F – receives a fraction of the earlier work’s performances, and no wonder. The Rhapsody has never lost its snap and sass. This despite suffering any number of indignities, from Larry Adler’s wa-wa harmonica arrangement to straight-backed symphonic versions by ‘classical’ pianists who couldn’t even swing if they were pushed.

Cut and paste

It is in the nature of the Rhapsody’s hasty origins that the piece never attained a final, definitive form. Gershwin recorded it twice with Whiteman’s band, in 1924 and 1927, but in an edit cut down to fit two sides of a 78. The orchestration even varies between those two early versions, so where should modern performers look in a search for the ‘authentic’ Rhapsody?

‘You can cut out parts of it’, Leonard Bernstein claimed, ‘without affecting the whole in any way except to make it shorter. You can remove any of these stuck-together sections and the piece still goes on as bravely as before. You can even interchange these sections with one another and no harm is done’.

Is it then, to quote the Cole Porter song of 1934, a case of anything goes? This talk does not go down well with Gershwin purists. I am not one of them, and anyway my beef with Leonard Bernstein is not what he says but how he plays. Too much Rachmaninoff, too much Bernstein, too much everything… except Gershwin.

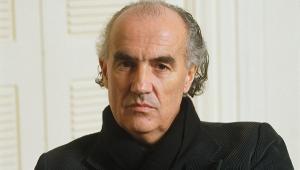

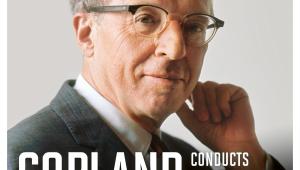

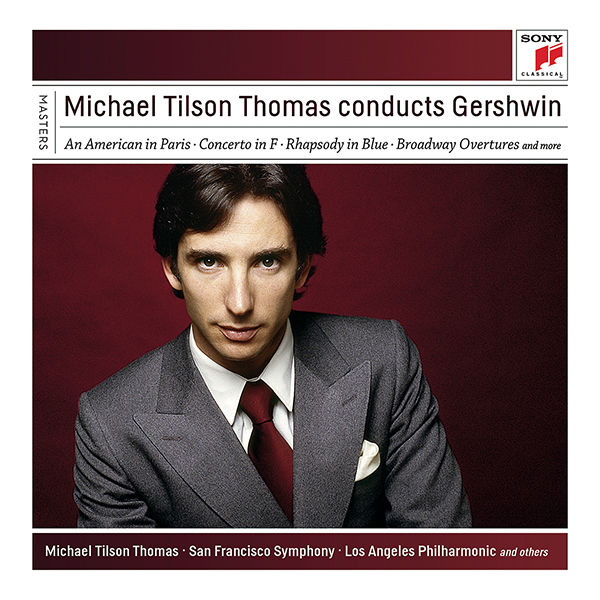

Above: Fellow American Michael Tilson Thomas conducted Gershwin for Sony and accompanied the composer from piano rolls

Did the composer have a grand crossover project in mind? He was at home with all these disparate styles because they were in the air he breathed, and he (and only he, perhaps) could assimilate them. When it came to fusing classical and jazz, Stravinsky and Milhaud had got there first.

Snap, cackle, pop

In fact, putting the text itself to one side, Gershwin left some invaluable advice about its performance. ‘The rhythms of American popular music are more or less brittle’, he wrote in the preface to his 1932 Songbook. ‘They should be made to snap, and at times to cackle. The more sharply the music is played, the more effective it sounds.’ Our Essential Recordings [see Essential Recordings below] all get the idea. Moreover, so did the black British pianist Winifred Atwell, recording Rhapsody In Blue in 1956 with bandleader Ted Heath. (Atwell’s Decca albums of both classical and pop repertoire deserve a modern remastering, although they are easily found on streaming services in the meanwhile).

Heath’s band is wind only, whereas most modern recordings attempt at least some variant on the ‘jazz orchestra’ devised by Grofé for Gershwin in 1924. Is that entirely a good thing? The Rhapsody never belonged in a box marked ‘classical meets jazz’, even if countless well-meaning musicians wanted it to. Tin Pan Alley, Broadway, ragtime, cabaret, blues, stride, Charleston… Gershwin smuggled in flavours of all these discrete ingredients, and ‘jazz’ as we might understand the term is among the least of them.

Higher fidelity

All the same, if you hear the piece as an authentically American counterpart to Ravel’s Concerto In G or Rachmaninoff’s Fourth, there are several full-orchestral recordings aspiring to higher fidelity than Bernstein. Gary Graffman romps through the solo part, with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (and Zubin Mehta) accompanying as though they have the score in their bloodstream. As they should. The close-up Sony sound also suits the piece better than the kind of ‘objective’ fidelity sought by European labels.

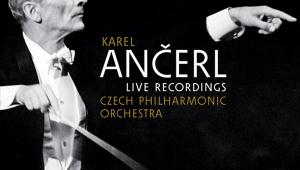

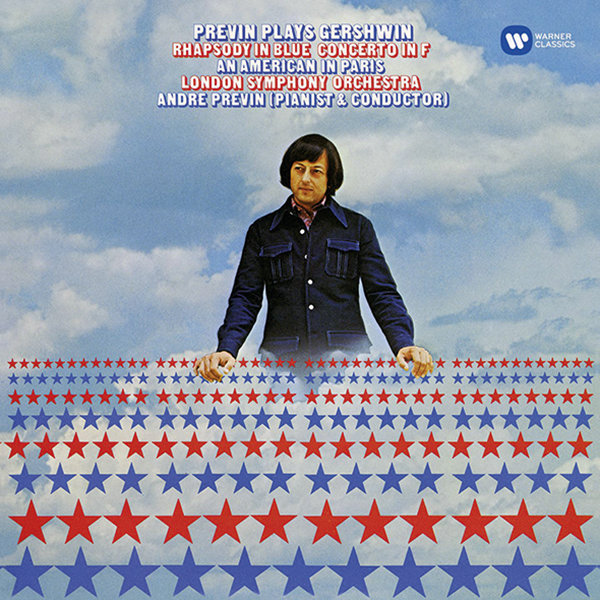

Above: For his 1971 debut on HMV, André Previn recorded the Rhapsody at Abbey Road

André Previn deserves special mention, as a pianist-conductor with more cred and more experience than Bernstein in the jazz clubs of New York. Of his three Rhapsodies on record, I prefer the first one from 1960, led by André Kostelanetz [RCA/Sony]. Later on, with the London Symphony Orchestra for HMV, Previn milks the central cadenza, though it’s hard to beat Gervase de Peyer in the opening clarinet solo. ‘Gershwin was musically a primitive’, Previn said in 1971 at the time of the HMV release, remarking on the ‘endearing naivety’ of Rhapsody In Blue: ‘There’s very little form, very little development… He was an American song-writer who wrote some of the greatest pop songs of all time’.

Staying true to ‘in Blue’

His digital-era Philips album reverts to the pulsing stride rhythm of 1960, now with neater and blander backing from the Pittsburgh SO on spotless studio form. Among Previn’s successors, meanwhile, Michael Tilson Thomas stands out as a musician who has studied and performed the full range of Gershwin’s work for music hall, stage and concert hall.

He revived the Second Rhapsody from 1931, when the composer attempted to make lightning strike twice (it didn’t). Whether guiding a modern jazz band to accompany the composer’s 1925 recording of the complete piano part on a piano roll, or playing his own solos, Tilson Thomas never gives the impression of patronising the piece with hoochie-koochie rhythms. Nor does he try to paper over the structural cracks with symphonic glue. The compilation of his Sony recordings is worth anyone’s money for letting Gershwin be Gershwin.

Essential Recordings

Gershwin, Tilson Thomas

Sony 88875170082 (7CD)

Tilson Thomas accompanying the composer’s pianola recording of the solo part, plus his own stylish and entirely modern version.

Gershwin, Paul Whiteman Orchestra

Naxos 8.120510

The original 1924 jazz-band scoring by Grofé, abridged to nine minutes, on a full collection of the composer’s own 78s.

Levant, Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy

Sony 88985471862 (8CD)

Another historical special: the star of the 1945 Rhapsody In Blue movie, in a box featuring many new-to-CD sessions by Levant.

Previn, London Symphony Orchestra

Warner Classics 5668912

Previn’s debut on HMV in 1971, marked by a classic cover and widescreen Abbey Road engineering, not denatured by remastering.

Donohoe, London Sinfonietta/Rattle

Warner Classics 3886802

Expertly fusing Donohoe’s Ravel-inflected pianism with Simon Rattle’s snappy handling of the original jazz-band scoring.

Grosvenor, Royal Liverpool Phil./Judd

Decca 4783527

Grosvenor (17 at the time) takes no prisoners in the solo part, backed by a slimmed-down, jazzed-up RLPO and high-impact Decca sound.