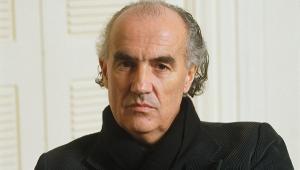

Charles Mackerras A Conductor For All Seasons

A few months ago, I was listening to Così Fan Tutte, in the 1993 Telarc version, and I thought, ‘Why didn’t I put this top of the pile in my Classical Companion [HFN Sep ’21]?’. It has everything: a cast who know each other and strike sparks off each other; 18th‑century‑style playing and decoration on modern instruments; studio finesse and ‘live’ tension. And behind these elements, there’s the dynamic hand and guiding spirit of Charles Mackerras.

Edinburgh brilliance

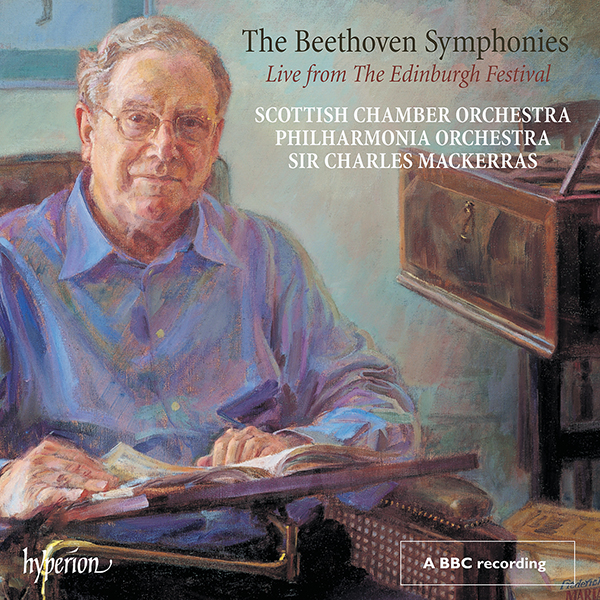

‘What’s the greatest recording of X?’ Some of you will be familiar with that question. I get it all the time. There really isn’t one, for ‘music that is greater than it could be played’, in Artur Schnabel’s phrase. But if they asked me where they should start with Così, I would point them to Mackerras. The same for the Beethoven symphonies, in the conductor’s second cycle on record, recorded live at the 2006 Edinburgh Festival under near‑ideal conditions. One symphony by itself, per day, so that the full attention of both orchestra and audience could be focused on each note, each chord, each phrase and transition, but also on each work as a chapter in a symphonic novel.

I never met Charles Mackerras, but a speech he gave at an awards ceremony, to accept a well‑deserved Lifetime Achievement gong, stayed with me. Without naming any of them, he managed to throw shade at all those maestros, young and very old, who become known as ‘great conductors’ through putting their own spin on the canon symphonies. You could have no idea of a conductor’s capabilities, he said, or they could have no idea of their own, until they did opera, in the pit.

Leading the way

Conducting opera was so much harder, explained Mackerras. It was more like three‑dimensional chess, coaching the singers not just in the notes and phrases but the roles too, accompanying them while also leading them, and simultaneously guiding the players through the orchestral texture, often in ‘new’ and unfamiliar music, whether written 300 years ago or yesterday. Then there were all the interpersonal relationships behind the scenes, with the stage director, the house management and so on. By comparison, standing in front of an orchestra to rehearse a Brahms symphony was a breeze. Everyone already knew the score, so to speak.

The virtue of replayability can’t become a goal in itself, as sometimes I feel it was with Karajan in his search to produce the single, definitive, technologically updated account of a work. What makes me return to Mackerras’s Mozart and Schubert and Janáček isn’t a matter of everything in its place, but a musicianship that encourages me to think about and engage with the piece freshly every time. You could say the same about Alfred Brendel’s playing, and perhaps it’s no accident that the Austrian pianist chose Mackerras to accompany him, in Vienna, for his farewell to a 60‑year career, in Mozart’s ‘Jeunehomme’ Concerto K271.

Decca’s recording of the occasion [4782116] should be considered an ‘Essential Recording’ of Mackerras, so the list on the page opposite feels somewhat arbitrary. Taking a mental tour through his discography, it can feel as though he recorded everything, with everyone.

Okay, that’s an exaggeration. Perhaps one reason Mackerras doesn’t tend to feature on lists of the ‘great conductors’ is his reluctance to set down symphony cycles, and by extension, to be defined by them. He had no time for Bruckner, and he tended to leave Shostakovich and Sibelius to others. He chose Handel over Bach, Richard Strauss over Mahler.

Self-evidently, Mackerras was a humanist to his fingertips, as well as a supreme pragmatist. Growing up in Sydney, he played piano and flute, but switched to oboe when he learnt that the city’s conservatoire was offering scholarships for students in ‘neglected’ wind instruments. In a 1959 article for Records And Recording magazine, he recalled a place and a time when a culture of classical music was still in its infancy. ‘During my musically formative years, the gramophone taught me more than live performance ever could.’

Mackerras liked to compare and contrast interpretations just as we do, and he made a distinction perhaps provocative to some HFN readers: ‘Musicians are always more impressed by the musical rather than the technical excellence of a recording... many of my favourite records are rather out-dated from the purely technical point of view’.

A glorious noise

No doubt, however, he had relished the widescreen potential of stereo sound when, six months before this interview, he had conducted almost every professional wind player in London, working through the night at a church in Cricklewood, in the first ever recording of the Music For The Royal Fireworks as Handel had conceived it, for a massive wind band. As reissued by Testament [SBT1253], complete with firework pops and bangs over the encored finale, it still makes a glorious noise, and could count as an unrivalled ‘first choice’ in the Mackerras discography. If he ever made a bad recording, I’ve yet to hear it.

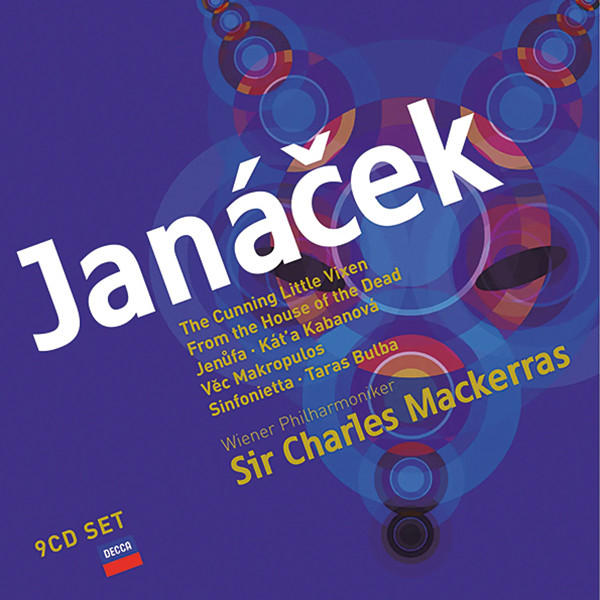

Foremost of omissions from the list opposite is the Decca box [4756872] of Janáček . Mackerras did for Janáček what Colin Davis did (at much the same time) for Berlioz, bringing both the operas, and native-language performances of them, into the mainstream. It’s too bad that he left behind no recording of The Adventures Of Mr Brouček, but his performances have gone down in the annals of English National Opera history.

Give me a ring

In the same vein, we are left with a meagre representation of his Wagner: an Australian Opera film of Die Meistersinger, and audio highlights of Götterdämmerung, on ABC Classics and Classics for Pleasure, respectively. Perhaps one day the Ring he conducted for ENO, as second fiddle to Reginald Goodall, will see the light of day. I wish there was a Martinů symphony cycle – but now I’m being greedy.

Whether in Janáček or Mozart or Gilbert & Sullivan, Mackerras was searching above all not for the fulfilment of a personal vision but the sound of a piece as the composer wrote it, in a down-to-earth spirit of authenticity that found expression in his work with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. In the Boydell Press monograph dedicated to his life and work, the bassist Chi-chi Nwanoku remembers him asking one hapless musician in rehearsal, ‘Why can’t you just get it... right?’ Their recording of Schubert’s ‘Great’ C major Symphony gets pretty much everything right, most of all in a Trio that almost weeps with nostalgic contentment, ‘those were the days’.

Essential Recordings

Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 1-9

Hyperion CDS443015 (5CD)

Nos. 1-8 with the Scottish CO, all outstanding, No.9 with the Philharmonia, slightly less ‘tight’, but still a Beethoven cycle for the ages.

Schubert: Symphonies Nos. 5, 8 & 9

Virgin (2CD)

Early recordings with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, and a model of ‘period’ sound in early-Romantic repertoire.

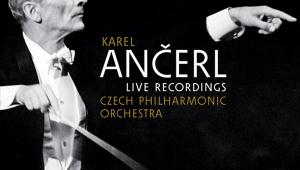

Life With Czech Music

Supraphon SU40422 (4CD & DVD)

‘Late’, Czech-made accounts of Janáček and Martinů, including a definitive Glagolitic Mass, plus a touching interview in English.

Mozart: Da Ponte trilogy, Die Zauberflöte

Telarc CR02008 (11CD)

The fruits of a long-term partnership with the Scottish CO and the Edinburgh Festival – and at under £30, an unmissable bargain.

Handel: Julius Caesar

Chandos CHAN3019 (3CD)

A high point of Mackerras’s ENO work, crowned by Janet Baker in the title role, but without a weak link in the cast.

Delius: A Village Romeo And Juliet

Argo/Decca 4833977 (2CD)

Mackerras as the true successor to Beecham, and another studio opera recording with all the intensity of a live staging.