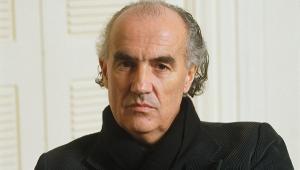

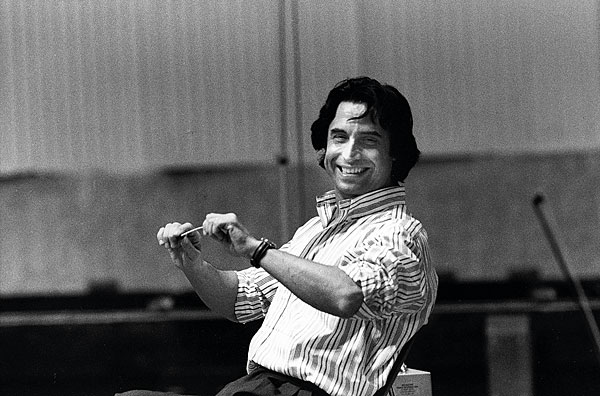

Riccardo Muti: Conductor

I remember how my heart skipped a beat one hot afternoon in 1989 when, browsing through the stacks of a secondhand LP emporium in London, I pulled out Riccardo Muti's recording of Tchaikovsky's 'Little Russian' Symphony. It was a noisy Italian EMI pressing – 'La Voce del Padrone' – and there was a huge scratch in the middle of Romeo and Juliet on Side A.

I didn't care, as all I wanted at the time was to complete a Tchaikovsky symphony collection on my teenage pocket-money budget. Even so, I still haven't heard another version to touch the finale's mounting excitement, the raw impact of the gong stroke before the coda or the electric timpani tattoo in the closing bars. It's classic Muti.

Neapolitan Dialect

Perhaps it's his age-defying black mane, but the idea of Muti turning 80 is hard to credit. He is a Neapolitan through and through, even if he spent formative years on the Adriatic coast and then trained at the conservatoire in Milan. There he made the transition from violin to conducting. 'It just seemed, suddenly, something I could do. I taught myself, really, though I learnt a lot from [Antonino] Votto, who helped Toscanini at La Scala. Toscanini and Furtwängler were the two biggest inspirations – totally different, but the control they had, of their minds, was the same.'

As early as his 20s, appointed music director of Florence's Maggio Musicale in 1968, Muti began to shape his own orchestral sound image. 'Very direct, very pure, sharp but not edgy', it was ideal for Italian music, and recognisably cast in the mould of Toscanini. In 1971, just turned 30, he made his debut at the Salzburg Festival, where he rapidly established a rapport with both the Vienna Philharmonic and the well-heeled audience.

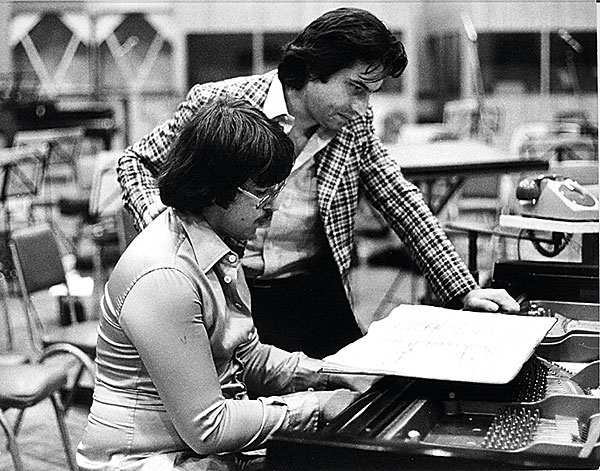

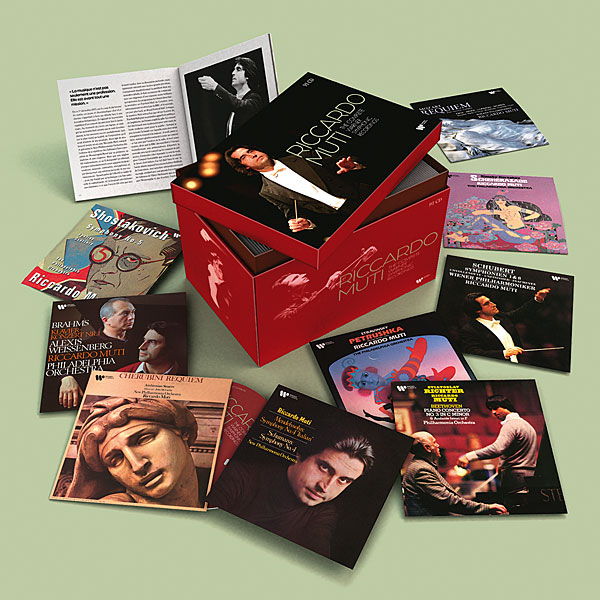

The following year he became chief conductor of the Philharmonia – then the New Philharmonia – at a watershed moment for the orchestra after its years with Otto Klemperer in charge. EMI signed him up and a string of late-analogue gramophone classics ensued, centring on the Russian and Italian repertoire which has always drawn the best from Muti's temperament.

Among his early recordings, Muti rated most highly the 'Scottish' Symphony of Mendelssohn and Verdi's Macbeth: 'With Macbeth, the balance between the orchestra and the singers is the nearest to my ideal. It's not a case of the singers being the stars and the poor orchestra just accompanying'.

Devotion To Verdi

The conductor's drive for technical perfection, sometimes at the expense of the music's inner life, more reliably strikes gold in operatic than orchestral repertoire – unexpectedly, you might think, when there is so much more to go wrong. Yet there is something palpable about his devotion to Verdi in particular, and his conviction over both the uniquely universal reach of the dramas and a symphonic approach to them that never treats the orchestra as 'mere' accompanist.

'If Wagner or Beethoven or Spontini were to tell me, "You were wrong, Riccardo!" I'd be able to take it', Muti wrote in his autobiography. 'But if Verdi were to tell me that – Verdi, to whom I gave my devoted love, and for whom I stood ready to retreat into an ideal orchestra pit and disappear – it would be terrible.'

In a long-planned handover, Muti took over from Eugene Ormandy at the helm of the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1980, refining but also polishing the ensemble's trademark deep-pile string sound. The focus of his recording activity followed suit, and while EMI continued to score artistic successes – a sensational Scheherezade and suites from Romeo and Juliet – it was Philips who picked the repertoire to record as carefully as Muti performs it.

As well as more Prokofiev there's an electric Strauss rarity [see the Essential Recordings boxout below], a retro-styled but beautifully 'heard' Brahms cycle and the original, orchestral version of Haydn's Seven Last Words – one of those reclusive bywaters Muti has returned to with almost obsessional devotion (he co-wrote a book on the piece) in a similar manner to his older colleague Claudio Abbado with Brahms's Rinaldo and Nono's Prometeo.

Muti liked to say he was looking for new music 'written with heart, not only with exercise', but this agenda has led him in unexpected directions beyond neoromanticism, to the Stravinskian Notturno of Irving Fine, the First Symphony of Penderecki ('a fantastic piece') and Schoenberg's Kol Nidrei [CSOR9011602, download only].

While a lot of the Chicago Symphony own-label albums in the latter part of his career have retained the perfectionist temperament but not the urgent expression of his analogue years, Muti gets the bit between his teeth for a pairing of works by the orchestra's resident composers, Anna Clyne and Mason Bates [CSOR9011401, download only].

From his tumultuous period in charge of La Scala (1986-2005: initially a dream job, eventually a nightmare) only Sony came close to documenting the spectrum of Muti's gift for drawing together the many strands of an operatic drama and pulling the singers with him through Karajanesque magnetism. Live at La Scala again, Spontini's La Vestale [88697527302, download only] is another of those immaculately cast and prepared rarities destined to sink without trace against the prevailing tide of performance values in early 19th-century music.

Since taking up the CSO directorship in 2008 (due to conclude next year) Muti has cut back his operatic and guest appearances, though a recent DG album documents both his enduring relationship with Salzburg, and his selective engagement with Bruckner (an unconventional, cantabile-led account of the Second, 4798180).

Number One

Films available to stream or buy as DVDs on Muti's own website at www.riccardomuti.com, document his increasing concern to pass on aesthetic values to a younger generation through the Orchestra Giovanile Luigi Cherubini which he founded in 2004. When Muti worked with the Australian Youth Orchestra in 2018, his apprentice Alexander Briger found it 'an incredibly intense and exhilarating experience... His eyes are mesmerising, trance-like, having every member of the orchestra in his sights'.

Sometimes Muti seems to push hard at the wrong door, or rather to open it and lock it behind him. At least outside his native Italy his efforts have not increased wider enthusiasm for full-scale stagings of Neapolitan farce, symphonic snippets of Nino Rota or hour-long Masses by Cherubini and Paisiello.

Folie de grandeur is an occupational hazard of the conducting profession, and Muti makes no apology for an aesthetic standpoint and working methods belonging to another age. 'The conductor must be Number One... That is the lesson of Toscanini.'