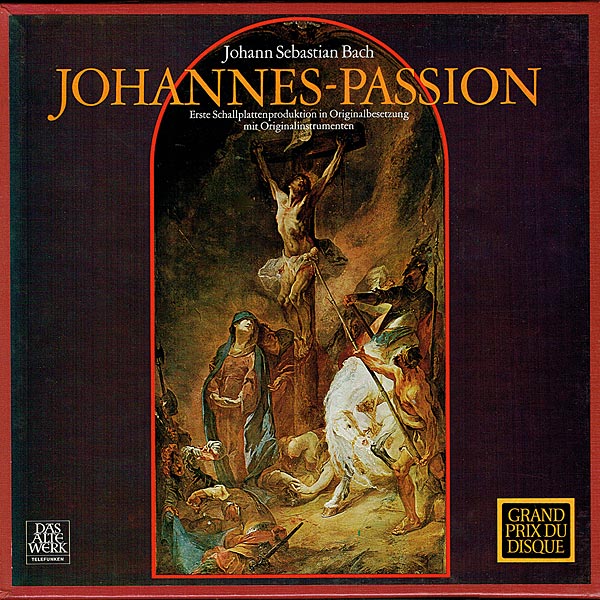

JS Bach: St John Passion

In telling the life of Christ, the four Gospels of the New Testament all build towards his betrayal, his trial, his death on the cross and resurrection. The first three events are known together as Christ's Passion, from the Latin passio: I suffer. Church composers had treated the text with varying degrees of freedom and complexity – the season of Lent being a time for quietude and restraint in every respect of life including liturgical worship – for centuries before Bach made his first setting of the Passion, during the early months of 1724.

Final Curtain

The first performance of the St John Passion on Good Friday that year now seems a watershed moment – for Bach's career and for sacred music, even for the way we listen. The greater part of church music up to that point had been written as 'music to pray by'.

Previous Passiontide Gospel settings of note – those by Tomás Luis de Victoria in Rome (1585), Heinrich Schütz in Dresden (1665) and Johann Theile in Lübeck (1673) respected the established conventions of distance between the congregant and the object of contemplation – ie, the death of Jesus. They were in many ways like icons, exquisitely wrought though essentially flat, inviting the imagination of the individual to lend the work perspective.

Bach tore down that curtain of distance, at once and for ever, with the St John Passion, and more specifically with the churning ostinato that sets the work in motion. This chorus demands, rather than invites, our attention – and really to the art itself rather than to its theological object, as a cathartic experience in the manner of a secular tragedy. The poetic text ('Herr, unser Herrscher') looks forward to the domination of God over the realm of earth, while Bach's music paints human need and suffering with a Caravaggio-like naturalism, establishing a tension that plays out until the final chorale's plea for release, imbued with an exquisite harmonic pain.

Despite their accumulating reverence for the past, 19th-century scholars scarcely knew what to make of the St John, and they left it largely alone. However, when Schumann revived the St John with his Düsseldorf choral society in 1851 he found it 'more daring, forceful and poetic' than the St Matthew.

On The Level

The recording of Schumann's edition conducted by Hermann Max [CPO 777091-2] has more than scholarly interest, with its flowery fortepiano continuo and an oaky string bass section for recitatives. The terse and brooding nature of the St John found a more lasting home, however, in the early days of the 'historically informed' performance revolution.

The Passion is designed to operate on several interlocking levels. First among them is the Biblical narrative of Christ's arrest, trial, crucifixion and burial recited in the words of the Gospel. At arm's length from the drama, the arias transport us to a lyrical and contemplative plane which reflects on these events. This meditative perspective then widens out to include a communal level provided by the chorales, where hymn tunes that are drawn from Bach's time crystallise the dramatic events in terms that are familiar.

A remarkable number of recordings satisfy the demands of all three levels, as well as reaching a more nebulous fourth at which the Passion becomes prayer and drama, a Christian prefiguring of Wagner's 'total work of art'. No less 'essential' than the five recordings listed below is Benjamin Britten's 1971 recording [Decca 4438592, download only], with an all-male choir of searing impact, singing like Peter Pears's Evangelist as if they believed every word of their English text.

Several other English tenors have made the role of the Evangelist their own (in the original German). In the 1980s and '90s pre-eminent among them was Anthony Rolfe Johnson, flexible in delivery for both John Eliot Gardiner's first [DG 4193242] and Nikolaus Harnoncourt's second [Warner, 2564690117, download only] recordings, and yet as urgent and concerned as if he were relating events that happened yesterday.

Among the next generation, Mark Padmore demonstrates a special affinity – at times a painful empathy – with the role on Gardiner's second recording [Soli Deo Gloria SDG712] and Herreweghe's first [Harmonia Mundi HMX290896569]. This last is no less 'essential' in its way for representing Bach's 1725 revision of the score, in which he inserted three new arias, tweaked the recitative and chorus underlays and – most radically – replaced the opening chorus with the choral fantasia which would become a keystone to Part One of the St Matthew Passion.

Baroque Swing

Masaaki Suzuki has also made two recordings, decades apart, both captured with notable immediacy by BIS. Many will prefer the tauter, more live-sounding second [BIS2551] with another fine English Evangelist, James Gilchrist; but I wouldn't be without the first [BISCD921/2], not least for the uniquely sweet and plangent contributions of the countertenor Yoshikazu Mera. This version also sets down Bach's final thoughts on his score, from 1749.

Among recent English recordings of the St John Passion, the Polyphony version led by conductor Stephen Layton [Hyperion, CDA67901/2] stands out for Carolyn Sampson's soprano and Ian Bostridge's Evangelist, and, less definably, for a sense of atmosphere retained from their almost annual Good Friday performances, recorded in a studio.

Less orthodox, no less informed than Peter Schreier by his practical experience of singing the Passion, is René Jacobs [Harmonia Mundi HMC802236/37, download only], imparting a French-Baroque swing to the closing lullaby and a bright astringency to the instrumental lines. None of these recordings suffers from distracting mannerisms, yet do they represent what Bach had in mind – and does it matter?

Special claims to authenticity are advanced by Philippe Pierlot [Mirare MIR136, download only], who returns with stylish conviction to the idea that Bach was writing for an ensemble of vocal soloists as well as instrumentalists. And also John Butt, the foremost Bach scholar-performer of our day, who presents the St John Passion in its original Good Friday liturgical context of chant, motets and voluntaries [Linn CKR419], albeit compromised by some dry and uningratiating solo singing.

Bach's score embraces all these approaches; no one will ever write a label for it as another entry in the 'early music' museum.