Haydn String Quartet: Op 76 No 2 'Fifths'

Aquick reminder: tonal music – indeed almost all western music for that matter – is built from 12 equally separated notes within the compass of an octave. Each tonality (C major, D minor, etc) uses eight of those notes in a scale: hence octave, 1-8. The root chord of each tonality (also called key signature) contains the first, third, fifth and eighth notes of the scale, 1-3-5-8.

The strongest, most stable relationship within these notes is 1-5, or 5-1. That's the main theme of this D minor Quartet in a nutshell, two falling fifths of A-D followed by E-A. So what is Haydn up to?

Virtue Of Simplicity

The composer often made a virtue of simplicity, but Op 76/2 takes melodic economy to a new level. With an understated virtuosity of technique, he challenges his listeners and his colleagues to marvel at what can be wrought from a humble pair of descending fifths. It's a taut drama of contrasts, often emphatic and abrupt.

Anyone who plays a string instrument knows that these are also tuned in fifths. There is a natural harmony between medium and message in the 'Fifths' Quartet that heightens the sense of a return to first principles. Haydn composed the Op 76 set of six quartets around 1796-7, at the summit of his fame. He was independent, a man of some means, living in Vienna but celebrated across Europe, committed only to writing an annual Mass for his former patron in Esterházy. Otherwise he focused most of his energies on writing his oratorio, The Creation.

The Op 76 quartets manifest an expressive freedom that seems to flower in Haydn's music after the death of Mozart in 1791. Take the third movement, beginning with a grimly relentless canon in two parts – the two violins playing one part in octaves, viola and cello following three beats later. Then comes an off-the-wall trio that is neither major nor minor but both, and sounding like a rusty squeezebox with half the keys jammed down.

Last autumn I heard Op 76/2 given live by a young Norwegian ensemble, Opus 13. It was a Goldilocks performance which made me fall in love with the piece all over again. Tempo, articulation, intonation, expression – everything was just right. Back at home, I pulled out my trusty Qualiton LPs of the Tátrai Quartet. The sound was comfortingly familiar, old-school Hungarian, but the performance read like a court report. The notes, my Lord, and nothing but the notes.

Goldilocks Scale

Hans Keller wrote of Op 76 No 2 as 'the least misinterpreted great Haydn quartet', implying it was somehow bombproof from odd ideas or wayward execution. He, of all critics, was entitled to his wrong opinion for there is a small and very sweet spot in this music between doing too much and too little with it. Go back to the Galimir Quartet and their recording from 1949 and you can hear them sawing through the Minuet. Accents, phrasing, dynamics, who needs 'em?

Then I turned to the London Haydn Quartet on Hyperion, within a much-admired, up-to-date period-instrument cycle of the quartets. The contrast with the Tátrai is so radical as to make a nonsense of the idea that only 19th century Romantic music invites extremes of interpretation. The first movement is more than twice the length: a matter of repeats, yes, but also tempo, and indeed the LHQ is the slowest version on record.

Tempo – the basic speed of the music – is one thing, and pulse is another. Quartets in older recordings tend to set a speed and stick to it, sometimes rather charging across the barlines ('too little' on my Goldilocks scale). Modern, period quartets, by contrast, shape the phrases with lavish application of rubato. In the case of the LHQ, scarcely a phrase is allowed to speak for itself without some expressive refinement or other, and the result compromises the momentum of the music, and the logic of its argument.

The Chiaroscuro Quartet likewise live up to their name. There is light and shade everywhere – a telling pause here, a surprise accent or dynamic there – but the painterly effects draw more attention to themselves than to the notes after a while. So, to put away Beckmesser's slate, there must surely be room for a middle way that doesn't sound like an artistic compromise.

And there is. A British tradition of plain-spoken, intelligent musicianship in Haydn was exemplified on record first by the Aeolian Quartet (Decca), then The Lindsays (ASV). Their modern successors are the Doric Quartet on Chandos, who follow modern period practice by taking all the repeats. They find gravity as well as 18th century elegance in the Andante theme and variations with a slower tempo than their predecessors.

Among older ensembles, the Tokyo Quartet (RCA/Sony) and Quartetto Italiano (Warner in mono, Philips in stereo) also score by not treating the Andante as a pleasant intermezzo. Their Minuet canon is stern but not aggressive; local character isn't on the menu. The opening of the finale brings with it another test – whether or how to build up to the first forte, which arrives at bar 20, and the Tokyos turn up the heat through each bar.

There is, though, much to be said for the more yielding tonal palette of gut strings in Haydn, a wider palette of vibrato, and period-style bows that lean in to the natural shape of the phrases. With these tools at hand, the first violinists of the Mosaïques and Festetics touch in the cheeky tail to the finale's main theme where other quartets make a meal of it with artful pauses.

Front Row Seat

The Festetics' intonation is slightly more suspect, and the recording more homespun, but they bounce the bow off the string perfectly in the Trio. As usual, the Naïve recording includes the sniffing of the Mosaïques leader Erich Höbarth – a deal-breaker for some, though not for me – and the compensating factor is a palpably vivid sense of sitting in the first row.

Both ensembles have the measure of the first movement as a grand narrative anticipating Beethoven, right up to the coda where Haydn seems to turn up, almost by chance, with the same 'fate' motif immortalised by the younger man in his own Fifth Symphony. Both of them also keep up the tension through the finale so that the D major coda rises above the usual, 'that's all, folks'. You won't find the Festetics except in a box set of the complete quartets – but then you acquire a lifetime's entertainment and food for thought into the bargain.

Essential Recordings

Quatuor Mosaïques

Naïve E8665 (2CDs)

Period-instrument quartet pioneers that are Franco-Austrian in sound and constitution, never taking Haydn for granted.

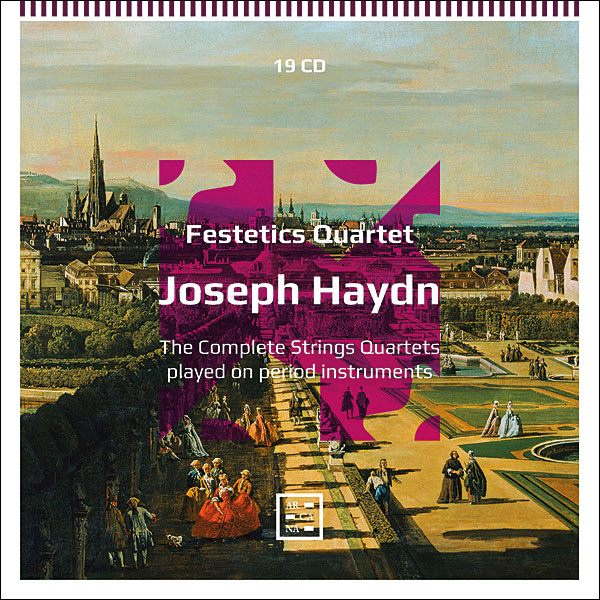

Quatuor Festetics

Arcana A207 (19CDs)

Still the only Hungarian period-instrument group to have recorded the quartets, and uniquely 'authentic' in that regard.

Quartetto Italiano

Warner 9029673920/Philips 4260972

Whether in mono (Warner) or stereo (Philips), one of the few 'classic' ensembles to go beyond playing by the book.

The Lindsays

ASV/Universal CDDCA1076

Some dated legato in the Andante, but otherwise this is a typically searching account with a properly Sturm und Drang finale.

Doric Quartet

Chandos CHAN10886 (2CDs)

Lots of ideas, most of them good ones, and a recording strong on inner parts in a realistic chamber-scaled acoustic.

Quatuor Modigliani

Mirare MIR506

Another excellent modern group, with a more compact sound and perceptive couplings of Bartók (No 3) and Mozart (K565).