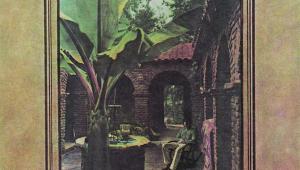

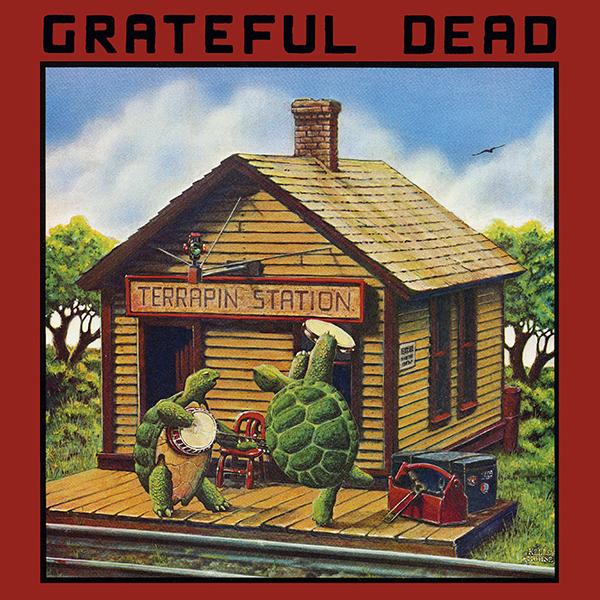

Grateful Dead: Terrapin Station

The Eno documentary recently shown in cinemas caused a bit of a fanfare because, characteristically of our eggheaded pal Brian, it wasn’t just any common-or-garden doc covering his illustrious career. Instead, it employed groundbreaking technology to accomplish something that had never been done before. Using generative software designed to sequence scenes and create transitions out of interviews with Eno and an archive of never-before-seen footage, each showing featured different scenes and music in a different order. Every time it played, it was a new experience.

Changing tunes

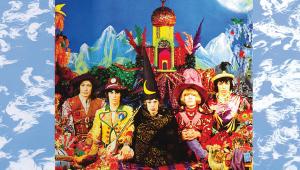

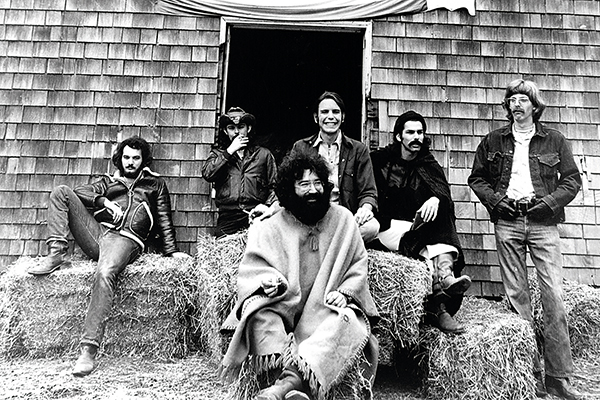

A cinematic first, no doubt, but it got me thinking about The Grateful Dead, because what Brian Eno had brought to the flicks, The Grateful Dead brought to the gig. The group, originally formed as The Warlocks in 1965 in the Bay Area city of Palo Alto, never repeated the same set twice, and never played the same song the same way twice.

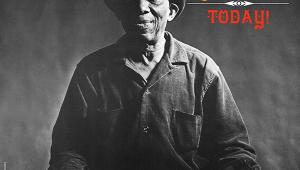

Above: The Grateful Dead in 1970 (l-r): Kreutzmann, McKernan, Garcia, Weir, Hart and Lesh

Partly this was down to technical inability – proficiency just wasn’t that high on their agenda, it was not the way the band rolled – but mostly it was down to believing that music is alive in the moment, vibing off the crowd and whatever chemical, emotional or personal state each band member was in at the time. They encouraged tapers in the audience to record their gigs for posterity. Personal favourites like ‘Friend Of The Devil’ were transformed over the years from acoustic folk to something approaching reggae.

Anyway, the very same improvisational approach which served them so well on stage over three decades proved an insurmountable impediment when it came to recording albums in the studio. The idea of creating a definitive version of a song was anathema to the Grateful Dead, just as finessing, over-dubbing and perfecting was not a feature of their DNA.

Occasionally they’d rein it in and hit a sweet spot, such as their 1970 albums American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead, which were early swerves into what has become known as Americana, and 1973’s Wake Of The Flood, which issued forth an hypnotic soporific groove. But often their studio efforts were exercises in frustrated compromise. Not to worry, as the band and their fans accepted that the best Dead LPs were the live recordings – Live/Dead, the triple Europe ’72 – while studio takes were looked upon as novelties featuring debuts for numbers that would doubtless be expanded and improved once they were taken out on the road.

Arista-cats

Constant touring, though, is an expensive and exhausting business and in 1974 the band called a hiatus. They also folded their own label, Grateful Dead Records, which they’d launched in 1973 to take total control of their careers, only to discover the day-to-day admin and upkeep too draining. Searching for a new home, they signed to Arista records, whose president, the legendary Clive Davis, was determined to market them to a wider audience. To that end, he insisted the Dead employ a producer outside of their familial circle – something the band had resisted up until this point. His nominee was Keith Olsen, who’d discovered Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham, eased them into Fleetwood Mac and polished them into multi-million-selling chart toppers. It must have made sense on paper, but what’s that saying about old dogs and new tricks?

Hammer and nails

Rather than tackle them on their own patch, Olsen had the Dead shifted lock, stock and barrel to Los Angeles and onto his own territory, Sound City Studios in Van Nuys. Things did not progress smoothly.

‘During the cutting of the basic tracks it was pretty hard to get every member of the band in the studio at the same time’, recalled Olsen. ‘So I sent someone out to the hardware store and got these giant nails and a great big hammer and as soon as everybody was in, we hammered the door shut from the inside... We didn’t have drifters from the other studios coming in to listen. We started getting work done’.

Olsen attempted to get the Dead to behave in the manner any normal band might – doing take after take in search of something solid to embellish – but the players bridled, resisted, and got bored. They were also wasted. Lead guitarist/ vocalist Jerry Garcia was hooked on a smokeable form of heroin and other band members were no saints either, which led to a slothful attitude to the project.

Above: Label of original UK LP on Arista Records

When the album was released in July ’77, it was not the Dead at their best. Side one comprised ‘Estimated Prophet’, where rhythm guitarist Bob Weir suffers under the illusion that he’s Bob Marley; a cover version of Martha & The Vandellas’ ‘Dancin’ In The Streets’; something unmemorable by bassist Phil Lesh called ‘The Passenger’; a soulless take on a trad tune called ‘Samson & Delilah’, and the worst number the band ever recorded, ‘Sunrise’, written and sung by Donna Godchaux because her husband Keith played keyboards. It’s horrible.

Mythical music

The eagle-eyed will have noticed the absence of Garcia on side one, but he makes his mark on side two. Running for 16 or so minutes in seven movements, and taking up the whole side, ‘Terrapin Part 1’ is a quasi-mythical thing from the pen of his regular lyric-writing partner Robert Hunter. What it’s about is anyone’s guess, but essentially there’s this lady who appears in a fire to a sailor and a soldier. She chucks her fan into a lion’s den and the lads are tested to prove who loves her the most. Nothing to do with terrapins, but hey-ho.

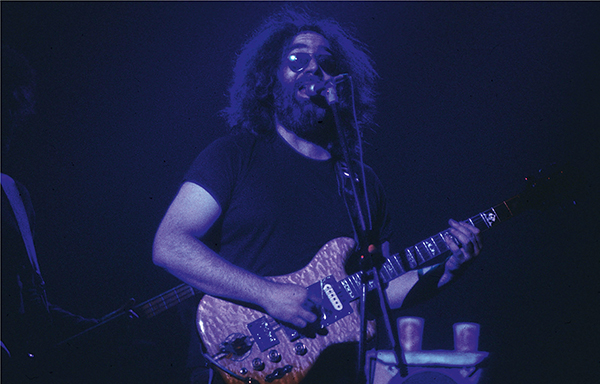

Above: Jerry Garcia on stage in May 1978 at the Veterans Memorial Coliseum

The piece as a whole is more prog than the Dead ever got before or since. Garcia’s voice is treated with this weird effect which makes him kind of warble and his guitar sound – which had hitherto been dextrous and clean – is a kind of synthesised sludge. To add insult to injury, Olsen took the tapes to London to add strings, horns and a choir without the knowledge of the band.

When the Dead heard the finished album they were horrified but too befuddled and bound by the business to do anything about it. Out it came, sounding more like England’s The Moody Blues than good ol’ Grateful Dead. Unsurprisingly, Terrapin Part 2 was never recorded.

Re-release Verdict

The Grateful Dead’s ninth studio album, originally released in July 1977 and certified gold a decade later, has been reissued by Rhino Records in both 180g black and limited edition green vinyl [R1 516251] versions. The set’s six tracks (including the seven-part ‘Terrapin...’ suite) have been remastering by Grammy award- winning engineer David Glasser at Airshow Mastering. David Lemieux, the band’s ‘audiovisual archivist’ since 1999, has overseen the reissue. HFN