Changing technology

It’s hard now to imagine what life was like when humans could only communicate over long distances by waving flags or mechanical arms for someone to see through a telescope, by lighting fires at the top of a hill, or relying on the homing instinct of a pigeon. But that’s how it was until the electric telegraph arrived in the 19th century.

It’s not even easy to imagine the pre-digital world of the mid-20th century. In 1965 the International Telecommunication Union published a 340-page centenary volume called From Semaphore To Satellite, telling the story of telecoms tech up to that point – which now seems like only the beginning.

Bright sparks

From Semaphore To Satellite deals with the long history of purely optical messaging before telling of some impractical attempts to use static electricity to relay information through the movement of pith balls or small pieces of paper. Eventually, though, it gets to when inventors were to harness ‘voltaic’ or current electricity.

By 1840, the electric telegraph had become an essential companion to the developing British railway network. Pulses sent through a wire from signalbox to signalbox conveyed messages visually by deflecting compass needles at the receiving end. Across the world, though, Morse code became the language of the telegraph.

Mid-century brought a rush to lay submarine cables connecting the continents. By 1860 telegrams could be sent from England to India and in 1866, after heroic efforts, a successful transatlantic cable was laid.

In the 1890s, the imperialist ‘Colossus’ Cecil Rhodes envisaged a grand African telegraph line, which, like the projected but never-completed Cape to Cairo Railway, was intended to link the British colonies on the continent from south to north. But technology was moving on. In his 1911 book Engineering Feats, Archibald Williams wrote: ‘The development of wireless telegraphy is... proceeding so rapidly that the completion of Rhodes’ scheme in its original form may not be justified. The upkeep of wireless stations is far less than the protection of thousands of miles of telegraph line against damage by human beings, animals, vegetation and storms’.

Pocket change

Visionaries have always pushed available technology to its limits, even if it’s soon to be replaced by something better. And a lot of audio technology has deep roots in telecoms. For example, in the early 1990s, when a team at Germany’s Fraunhofer Society developed MP3 coding for music, they were building on earlier work on data compression and perceptual coding by Bell Labs and Nippon Telegraph and Telephone.

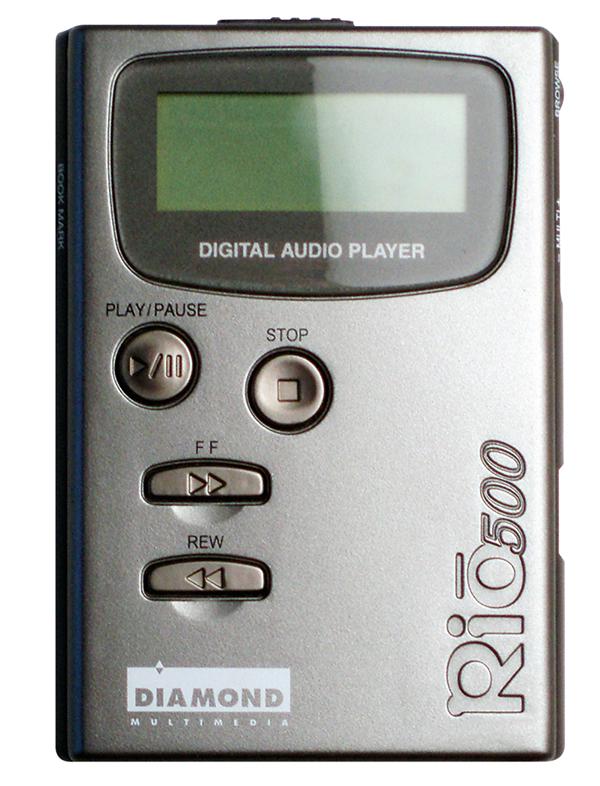

Later that decade we had the Internet and mobile phones, but only a few would have predicted that one day the phones would do everything. You could get MP3 music from the ’net, but to carry it around you still needed a pocket audio player like the Rio PMP300, which could initially store just 30 minutes of songs.

Then came the legal battle over Napster’s peer-to-peer file-sharing, and for a time the record industry was almost in meltdown over copyright and piracy issues. But then Apple launched iTunes and the iPod player in 2001, starting an era in which users could legally buy music files online. The first iPod had 5GB of storage and was said to hold 1000 songs.

By this time mobile phone users could get some access to the Internet using the Wireless Application Protocol, but WAP phones were soon made obsolete by the arrival of truly capable smartphones.

Even so, I still remember how, when Chord Electronics founder John Franks was launching the company’s HUGO personal DAC/headphone amplifier, he surprised by pointing out that mobile phones would soon have terabytes of memory, enough to store a user’s complete music library. With 256GB not uncommon, that day is close.