Return to Ronnie Scott’s

Barry Fox heads along to Ronnie Scott’s in London to find out how the legendary live music venue has revamped its sound system, and why it’s in a ‘war of attrition’ with drummers...

'Big Hi-Fi’ is a neat way to describe a clean and powerful sound system used to assist live sound in a music club or small hall. BHF does not come cheap or easy, which is why so many music venues wreck music.

The Ronnie Scott’s jazz and rockish-pop club in London’s Soho has recently been refurbished and I kept thinking the words ‘Big Hi-Fi’ when I went to one of the re-opening events – the premiere of Inferno 67, an extraordinary jazz theatrical show by trumpeter/bandleader/arranger/composer Guy Barker.

Taking control

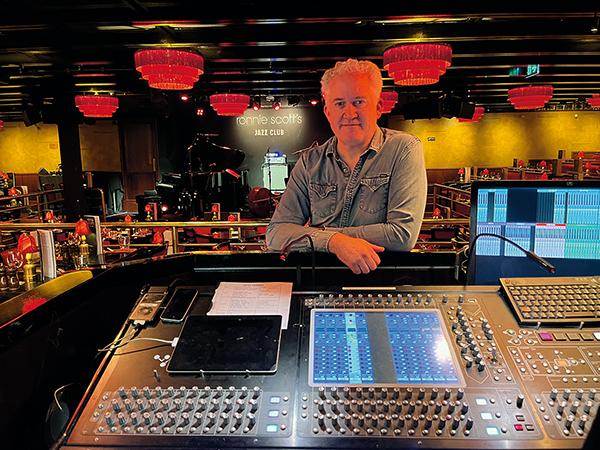

A few days later I went back to talk with Technical Director Miles Ashton about the refurbed sound system that had done Barker’s big band music so proud.

Ashton thinks of the Scott club as now having ‘a studio control room vibe’. Soft furnishings and ceiling tiles create a dead acoustic that remains near constant regardless of whether there’s a sold-out full house with ‘225 mobile baffles’ (aka customers) or the club is empty during daytime sound checks.

‘Ronnie’s’ currently has a pool of around 12 sound engineers, all of them freelance and most with some kind of formal college training. Miles Ashton, however, ‘learned on the job’, mixing the live and recorded sound for the National Youth Jazz Orchestra created by his father Bill Ashton. He later got his wider-than-NYJO break in 1987 when Jon Hiseman, drummer with cross-over group Paraphernalia, heard the NYJO performing in a barn-like pub in Rayners Lane.

Recalls Ashton: ‘Jon Hiseman liked the sound and offered me the job of Paraphernalia’s sound engineer. One of my first gigs was at Ronnie’s.

The club’s sound system has for many years been based on d&b audiotechnik gear from Germany, a brand Ashton remembers he first came across in 1990 while on tour with Paraphernalia. ‘Their [sic] amps and loudspeakers work together as a system, much like a Bose PA. d&b amps will only work with d&b speakers and vice-versa. The amp is continually sensing the load.

‘You can’t blow up a d&b system, however hard you try. The amp will never overload the speakers. They are bulletproof because d&b test them to destruction in a bunker in Germany, feeding them 24 hours a day with distorted garage band music.’ Ronnies uses a spread of four d&b point source speakers handling up to 136dB SPL for the mid and top end. In-fill speakers in the ceiling and behind the audience use digital delays to time-align with the front, main speakers.

Making waves

Previously, like most venues, the club used two large subwoofer enclosures, with 18in drivers, one at each side of the stage. This can create uneven bass where the wavefronts meet. Now there are six 12in subwoofers, each with 127dB handling, in a ‘distributed line array’ of six concrete bunker cavities built along the front of the club’s stage. Again, signals are time-aligned by digital delays, increasing from the centre out so the six subs focus into a single wavefront.

For mixing, Ronnies uses a DiGiCo desk with multitrack signals multiplexed (at 48kHz/24-bit) through a single fibre cable, which runs both ways around a loop. This offers a degree of redundancy, because if the fragile fibre is ever broken the signal just travels the other way.

Acoustic bass is miked with a DPA 4099 condenser mic clipped near the bridge; electric bass ‘guitars’ are double-miked, with an acoustic mic close to the player’s own bass amp speaker and the feed from the guitar also injected into the mixing desk. The mixing engineer can then decide which feed or mix to use.

‘The golden rule is to do what the musician asks for’, says Ashton. ‘Use whatever mics they want you to. You don’t have to mix it all in. We are in a constant war of attrition with drummers. If there are no mics on the drums they will beat the hell out of them. But if we put mics on the drums they play quieter. And we don’t have to turn them on...’