Borys Lyatoshynsky: Ukrainian Symphonist

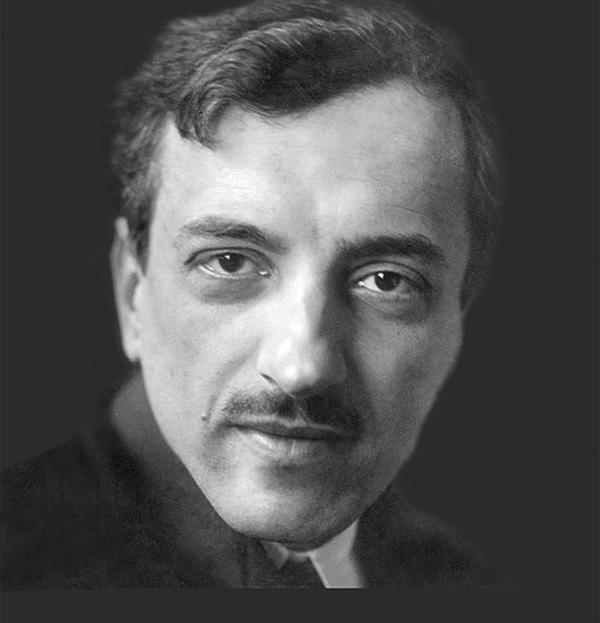

Ukraine had been a neglected outpost of Imperial Russia long before it was incorporated within the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics (USSR) in 1922. Accordingly, born in 1895 into a prosperous and cultivated middle-class family, Borys Lyatoshynsky received a typically thorough state education at one of the boys' schools in the city of Zhytomyr, in north-west Ukraine.

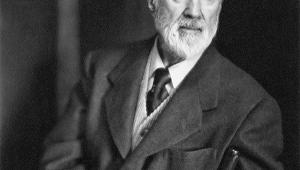

His musical talent had been evident from an early age, and alongside studies in law he took classes at the conservatoire in Kyiv with its professor of composition, Reinhold Glière. Putin's invasion has made a 'Ukrainian composer' out of Glière, just as it has (with bitter irony) turned the world's attention to hitherto unexplored avenues of Ukranian culture.

Fierce Storms

Reinhold Glière himself would hardly have recognised the term, being of Polish and German descent, and another composer writing in the dog days of the Russian Empire and the false dawn of the Soviet era. Even so, he understood that Kyiv afforded the seclusion to be himself, along with the drawback of obscurity. He wrote to his talented pupil: 'For a contemporary composer, and a young one at that, to live in a backwater like Kyiv means almost burying oneself'.

Lyatoshynsky chose to stay put, married happily to Marharyta Tsarevych, a fellow conservatoire student. By the age of 27, he was teaching classes at the Conservatoire himself. In that capacity he became a mentor to the next two generations of composers, including the best known Ukrainian composer of our time, Valentin Silvestrov. Like all the best teachers, Lyatoshynsky guided the talents of his students rather than drilling them. Presented with a piece of bristling modernism by Silvestrov, Lyatoshynsky simply asked him, 'Do you like this music?'.

His own music had acquired its voice amid the fierce storms and competing ideologies of music in the first decades of the last century. He wrote his First Symphony as a graduation exercise, conducted at its premiere by Glière. Its expansive three-movement form, soulful clarinet melodies and lush orchestration luxuriate in the 'Silver Age' opulence of Rachmaninoff, Scriabin and indeed Glière.

Five years later, he was setting Shelley in a translation by Balmont. To pass such bitter comment on the seductive danger of tyranny and the impermanence of power was a brave act in the Soviet Union of 1924. The Second Symphony of 1928 plunges head-first into the bracing world of early-Soviet modernism, which was epitomised by Shostakovich's Fourth of six years later, and received a similarly chilly reception.

Lowest Ebb

Because of his talent, Lyatoshynsky became the main casualty in Kyiv of the dismal Soviet culture war fought over 'formalism'. By composing (and no less importantly teaching) with an artistic freedom that recognised no Iron Curtain between Soviet culture and modern Europe on the other side, he was branded 'the most characteristic representative of bourgeois individualist urbanism'. After the infamous decree passed in 1948 by the Soviet Union's Culture Minister Andrei Zhdanov, Lyatoshynsky wrote in despair to Glière: 'As a composer I am dead, and I do not know when I shall be resurrected'.

Yet it was at this lowest ebb in his fortunes that he wrote some of his finest music. Composed for the 25th anniversary of the Revolution, Lyatoshynsky's Third Symphony had a triumphant premiere in Kyiv in 1951, but its tragic ending met with hostility from Soviet apparatchiks. Lyatoshynsky was accused of fighting against the war 'not as a Soviet supporter of peace, but as a bourgeois pacifist'. He took such public criticism and humiliation badly, but spent the next three years labouring over a Soviet-friendly revision. The new, happier-ending Third was duly taken up by Yevgeny Mravinsky, who wielded unique authority within Soviet musical politics as chief conductor of the Leningrad Philharmonic.

Any listeners familiar with the revolutionary apparatus, the battleship-grey orchestration and stealthy resistance of Myaskovsky's symphonies will recognise a kindred spirit in Lyatoshynsky's Third. The introduction's grinding dissonances and rugged breadth announce an epic struggle played out over the traditional four movements. Even in its revised ending, the composer Kabalevsky heard joy, but 'it is the joy of a tormented person'.

These were strange times, when a composer might receive the Stalin Prize one month and have his relatives arrested the next. Disinclined to both conformism and rebellion, Lyatoshynsky got on as best he could. He liked to quote a cynical old aphorism: 'Listeners love music but don't understand it; composers understand it but don't love it; critics neither love nor understand it.'

Stalin's death in 1953 made an ambivalent impact on the music of Lyatoshynsky as it did on Shostakovich. With more freedom to express themselves, they found a new, more straightforward idiom, at least in their symphonies. The notes of Lyatoshynsky's Fourth are painted in capital letters and poster-paint colours as they are in Shostakovich's Eleventh. The Fifth goes further still with its 'Slavonic' narrative and noisy, bell-capped coda on the national theme used by Stravinsky for the apotheosis of The Firebird.

Our grasp of Lyatoshynsky is limited by the catalogue. Probably for both political and commercial reasons, his two operas were never recorded. He wrote incidental music for stagings of Shakespeare and cutting-edge film-makers, as well as a good many choral pieces and folk settings which would have ingratiated him with the authorities. There is no available cycle on record of his four string quartets.

Heroic Legacy

Easiest to find on CD, his pair of piano trios is a fitting continuation of the Tchaikovsky-Rachmaninoff line. The Second is a wartime work, conceived on the grandest scale, memorial in tone unlike the heroic tone of the Piano Quintet on Ukrainian themes from the same time. From more adventurous times, the Violin Sonata of 1926 bears comparison with Prokofiev for its biting harmony and defiance.

Lyatoshynsky's death in 1968 is commemorated at his museum-like residence, complete with a large, ornate clock that is stopped at the hour and minute of his passing. One of his pupils was the composer Yevhen Stankovych: 'Lyatoshynsky was an extremely important figure in the art of music. He amazed me with his colossal musical erudition, his broad knowledge of the past and present'. Shostakovich paid tribute to the memory of 'a great composer and an outstanding teacher'.

Essential Recordings

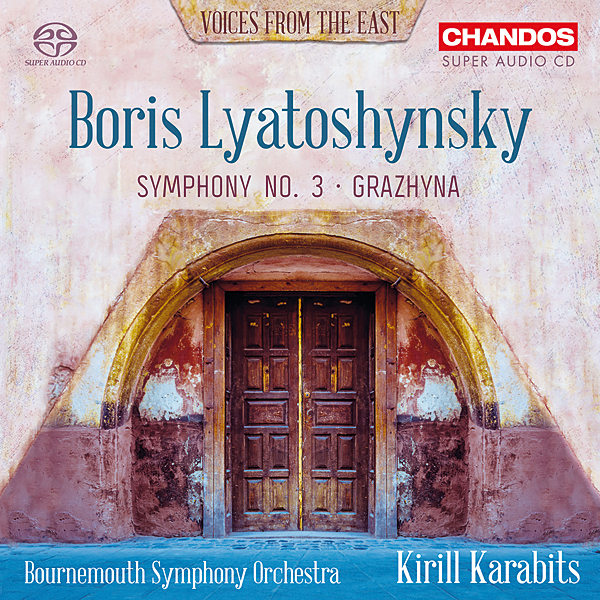

Symphony No. 3, Grazhyna

Chandos CHSA5233

Lucid sound and blazing playing from the Bournemouth SO and their Ukrainian chief in the composer's finest symphony.

Symphonies Nos. 4 & 5

CPO 999183-2

The rebarbative grandeur of Lyatoshynsky's later symphonic writing is given full value by Roland Bader and the Krakow Philharmonic.

Symphonies Nos. 1-5

Naxos 8503303 (3CDs)

Boomy sound and rough but authentically committed playing from the Ukrainian State SO under long-time leader Theodore Kuchar.

Violin Sonata

Labor LAB7095

Solomiya Ivakhiv and Angelina Gadeliya pour heart and soul into this spiky product of the composer's edgiest period.

Piano Quintet

Naoxs 8579098

An invaluable collection of modern-Ukrainian piano quintets, joining the dots between Lyatoshynsky, Silvestrov and Victoria Poleva.

Ozymandias, etc

Toccata TOCC0053

Accompanied by Alexander Blok (not the poet!), the bass player Vassily Savenko brings a haunting authority to Lyatoshynsky's songs.