Audiostatic Monolith II loudspeaker

John Atkinson clears space for a towering full-range electrostatic speaker from the Netherlands as Audiostatic’s Monolith II lands on UK shores

John Atkinson clears space for a towering full-range electrostatic speaker from the Netherlands as Audiostatic’s Monolith II lands on UK shores

Blame Stanley Kubrick. Until 2001 burst onto our cinema screens, the lay conception of outer space had settled down as a mixture of flying saucers and little green men. Why green? Why little? But this was irretrievably displaced by an alien ex machina presence that set the style for, yes, the shape of electrostatic loudspeakers to come.

The sight of that monolith, teaching man’s forerunners about evolution, Diet Coke and how to drive a Sinclair C5, for some reason must have struck a responsive chord in loudspeaker engineers’ hearts, for there are now several models looking uncannily like smaller versions of Kubrick’s TMA-1.

Hidden panel

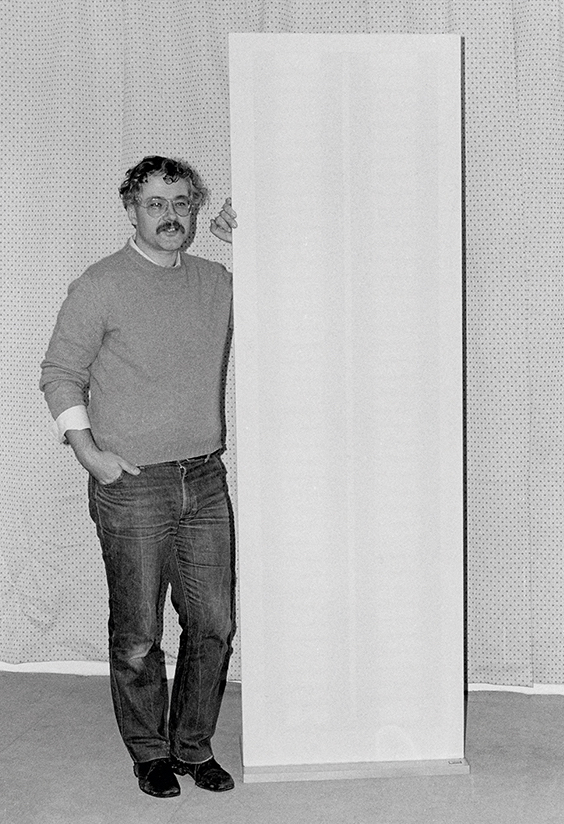

Somewhat slimmer than the 2001 archetype is the Audiostatic Monolith I electrostatic loudspeaker from Holland [HFN Jun ’84]. Over 7ft tall, but only 15in wide and less than 2in thick, this £2000 pair of loudspeakers was one of the most elegant to have graced my lounge when I borrowed the review pair 18 months ago. The styling and finish caused them to disappear in the presence of conventional furnishing, and the height and wide dispersion gave the solidity of lateral imagery typical of line-source loudspeakers.

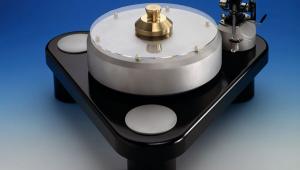

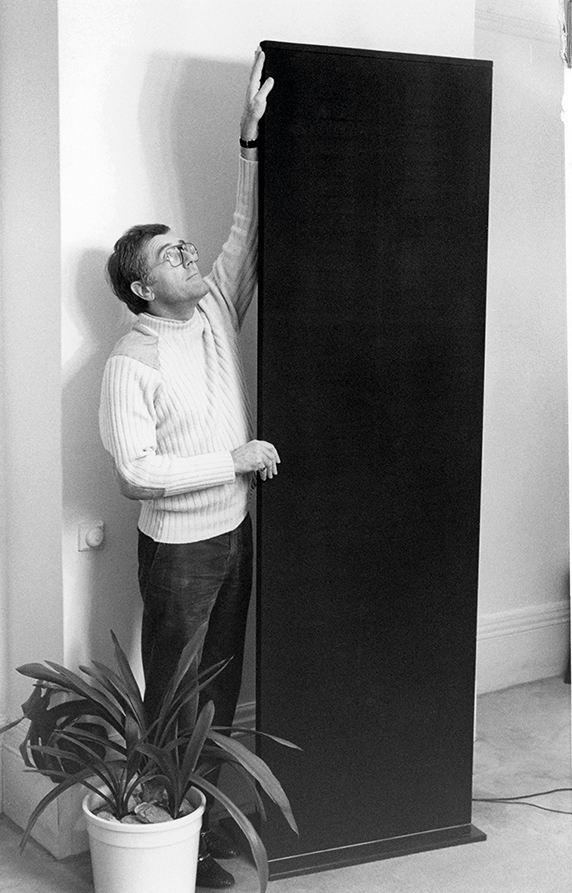

Audiostatic founder Ben Peters stands alongside the 7ft-tall Monolith II speaker, which cost £2990 on launch

The ideal, infinitely narrow, line source –extending from floor to ceiling – produces a cylindrical wavefront which alleviates the HF beaming problems with wide plane-wave radiating panels. Coupled with this scalpel-sharp imagery was a transparency to the upper midrange and treble that remained unrivalled until the day I heard the Apogee Scintillas.

However, as the measurements in our Jun ’84 review revealed, the Monolith I does like to be in the vicinity of side walls if the balance is not to become a little bass-shy. In the asymmetric listening room that I was using at that time, I couldn’t tune the low frequency balance to my satisfaction, so the otherwise impressive Monolith I went on the back burner as far as my personal listening was concerned.

I hasten to add that this incompatibility did not reflect negatively on the Monolith. Dipoles are particularly troublesome in this respect, and some rooms just don’t seem to like panel loudspeakers. The bass balance proved not to give problems in more conventional rooms, and the Monolith I paved the way for a loudspeaker which might have been purpose-built for rooms giving compatibility problems. Enter the £2990 Monolith II.

Wide and clear

Although the same height and thickness as the I, the Monolith II is almost twice as wide, designer Ben Peters – a man with hi-fi street credibility, he plays trumpet in a Dixieland band – having added an extra panel to act as a bass radiator. As with all the Audiostatic full-range electrostatics, there is no electronic crossover; rather, mechanical decoupling is used so that not all the radiating area works at all frequencies. In the II, the bass panel only handles frequencies below 300Hz, while the other panel handles the entire range. Above 3kHz, the working area narrows to just 2cm, giving usefully wide treble dispersion – there are no head clamps necessary here.

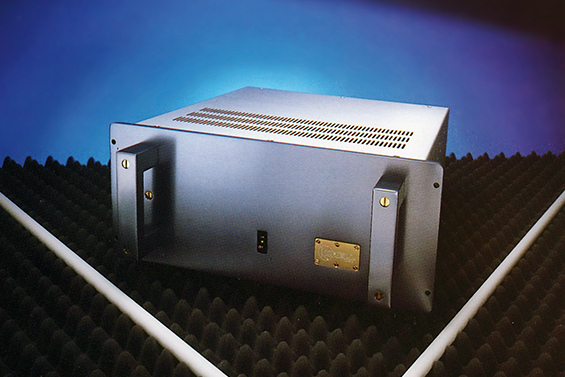

'Essential partner for the Monolith II’ – a Beard P100 power amp seen stacked above a Beard P505 preamplifier. Rated at 100W per channel, the P100 was built around KT88 output tubes

By adding what is in effect an electrostatic sub, the backwave cancellation frequency is lowered, due to the increased width. Meanwhile, the total air mass that can be moved is increased, and as the bass range is shared with another driver, the main panel no longer undergoes such large bass excursions, which will lower levels of Doppler distortion in the human voice range. The II has a cleane

r midrange than the I, presumably due to this effect.Feel the load

Apart from room interaction difficulties, electrostatics can be notoriously insensitive – remember the Stax ESL-F81’s 73dB/1W/1m – and to compound this, can present very awkward loads for the amplifier to drive. A transformer-coupled electrostatic loudspeaker has a fairly low impedance at high frequencies, perhaps under 1ohm, and a high impedance at low frequencies, which tends to make life hard for amplifiers. The low impedance can lead to a high current demand at frequencies where the amplifier would prefer an easier life, and valve amplifiers in particular don’t like to see a load of hundreds of ohms at low frequencies, which is effectively an open circuit.

Flat’s the way

In order to circumvent this problem, an early full-range Audiostatic speaker, the E240 (which some may remember producing sweet sounds at the 1980 Cunard show) was active, being directly driven by an integral valve amplifier working with an anode potential of 5000V. However, this was not very reliable, with moisture and hum problems resulting from the tubes having to work at high voltages. So Ben Peters went over to a passive version of the speaker, driven via a transformer. The sensitivity was low, around 75dB/1W/1m, though, and the design still suffered from the unfriendly impedance, so Ben put into practice an idea he had been mulling over.

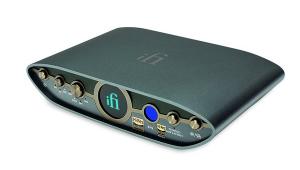

Rated at 50W per channel, Krell’s solid-state KSA-50 was the first power amp the author used when listening to the Monolith IIs. Like the Beard P100 it was hooked up to an Audio Research SP-10 preamp

He added another transformer and a passive network to the drive transformer. This extra circuitry has an impedance ‘mirroring’ that of the loudspeaker – it has a low impedance at low frequencies and a high impedance at high frequencies – giving a resultant impedance curve which is sensibly flat. That for the I, for example, is around 5ohm below 300Hz, around 16ohm at a few hundred Hz and 3-4ohm at HF. Not only does this make the speaker an easier load to drive, its sensitivity can be raised to a more normal 86-88dB/1W/1m.

This sounds very similar to the historic technique of conjugate load matching, which KEF revived for its R104/2, but Audiostatic has managed to patent this ‘Mirror Drive’ principle for electrostatic loudspeakers, which may cause problems for other manufacturers.

![]() Flat's the way

Flat's the way

A house move prevented my auditioning the Monolith IIs in the same room as I’d tried the Is, but how did they fare in the new space? I waited a day after plugging in the little mains plug-mounted transformer, which provides the polarising voltage, before serious listening. The speakers were hooked up to a Krell KSA-50 power amp, preamp was the usual Audio Research SP-10, source was initially the Meridian CD player and the first track played was naturally Also Sprach Zarathustra.

Lack of bass? That low C organ pedal note rolled across the floor, pausing only to massage my chest before letting itself out of the French windows, where it almost convinced the birds that a small earthquake had struck Sussex. If anyone tells you that electrostatics have no bass, send them to listen to what the Monolith IIs can do when booted around by an amplifier with real moxie power. On went the 12in single of Joe Walsh’s ‘Rocky Mountain Way’, and then Tina Turner’s ‘We Don’t Need Another Hero’... Luckily, the neighbours then came home – I could feel the folds in my brain straightening out.

Some music that demanded subtlety rather than sheer bass extension and power handling was called for. So out came the Borodin Trio’s recording of Rachmaninov’s 'Elegiac' Piano Trios [CHAN 8341].

Shaken ’n’ stirred

This is a favourite of mine, despite a rather exaggerated perspective. The Audiostatic Monolith IIs presented such a precise image, with such unambiguous delineation of depth and such a transparent definition of the finer detail, that what I had previously thought of as a discrepancy between the acoustics of the strings and piano evaporated. Yes, the violin and cello are somewhat close compared with the piano further back, but on the Monolith IIs, all the instruments are now set within the same acoustic space. This was similarly noticeable on the percussion-oriented album Däfos, all the various shaken, hit and dropped instruments being securely spatially locked in place.

This is not to say that I was completely satisfied. Although there was sufficient bass, this was not quite as well controlled as that of the Apogees – perhaps the main panel should have been fed via a high-pass filter – and it took a little time to find the best position in the room for both balance and control.

Brian Smith of Audiostatic’s UK distributor Presence Audio with the Monolith II sporting a black frame and grille cloth

Despite the lack of mid coloration, the sound was a little forward in the presence region, the measured in-room response showing a broad plateau between 2kHz and 8kHz around 3dB above the midband level. While aiding the retrieval and decoding of recorded ambience, shining the light a little brighter, this was less than forgiving of recordings already hyped in this region. Eventually, I took distributor Presence Audio’s advice and drove the Monoliths with paralleled Beard P100s, a valve amp less incisively neutral than the Krell, but one combining a sweet tonal delicacy with more than enough power to drive the speakers to levels approaching the realistic.

Conclusion

While expensive, the Monolith II is 60% the price of the Apogee Scintillas; it is best thought of as offering an alternative approach and balance to the similarly priced Magneplanar MG III. On the plus side, as well as fine aesthetics and finish they offer excellent bass extension, high power handling, a superbly transparent midrange, and deep imagery, among the most laterally precise I have heard.

Against this must be put its treble balance, which is unforgiving of faults in ancillary equipment and recordings, and the difficulty in achieving the optimum bass balance and tuning in some rooms. If you are prepared, however, to put together a system to exploit to the full what these speakers can do – and the Beard P100 seems an essential partner – then you will enjoy your records for a long time to come.